Moki, Tan and Jannies were babies at the close of the American war in Vietnam in the 1970s. Their mothers were Vietnamese. Their fathers were American soldiers. In one way or another, they were all abandoned.

Now, the search for their birth families has brought them together. Here are their stories.

Moki

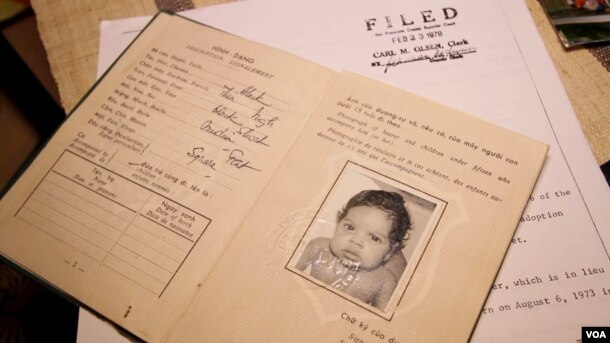

Moki was at an orphanage in Vietnam when her adopted mother saw her.

Maria Eitz was single, but she had already taken in two mixed-race Vietnamese boys. Now she wanted her sons to have a sister.

After all, Eitz knew what it was like to be an orphan. She was left in Germany without her parents at the end of World War II.

The women who worked at the Can Tho orphanage tried to show Eitz some mixed-race babies with light skin. But Eitz saw only a dark-skinned girl with a big stomach and curly hair.

“That's my daughter,” Eitz said.

She wanted a girl who looked like her two black-Vietnamese adopted sons. And, she said, she wanted a girl whom nobody else wanted.

Eitz named her daughter Moki and brought her to San Francisco, California, where she and her sons lived.

“I remember being very happy as a kid,” Moki said.

Her house was full of other children. Her adopted mother eventually married a kind, respectful man. Moki attended a good school and had close friends.

Still, Moki thought about finding her biological parents. She imagined they had a love story. Their romance was like a fairy tale, she thought - like the show “Miss Saigon.”

When she was 18 years old, Moki herself became pregnant. Even at that young age, she was excited to have her own child.

“I wanted my own blood,” Moki explained.

She gave birth to a daughter, Kaitlin, in 1992.

The following year, Moki found a growth on Kaitlin's neck. She brought her daughter to the doctor.

But she could not tell the doctor her family's medical history.

Mokie thought, “This is my child and I don't know what's wrong. And the doctors don't seem to know what's wrong. And I have no information.”

The thought scared her.

Now, she had to find her biological parents. The search was a medical necessity.

Tam

Tam did not have as happy a childhood as Moki did.

When he was three days old, someone left him in a box outside a bar. Many Americans soldiers spent time at the bar, located just outside Tuy Hoa Air Base, near the city of Nha Trang.

Whoever left the baby was telling the American soldiers that the boy belonged to one of them. But none of the men claimed the baby.

So the bar's owner, Nguyen Thi Ngoc Van, adopted him. She called him Nguyen Tam and raised him as her only son.

When Tam was only 11 years old, Ngoc Van left. She went with a boyfriend to Pleiku. Tam stayed with his adopted grandparents.

But Tam remembers his adopted grandparents did not welcome him. “You don't belong here,” his grandmother said. “Any day you are here you have to work for the food you eat.”

In the late 1980s, a Vietnamese official came to talk to Tam's grandparents. The official explained that the U.S. government had created a new program. It permitted the orphaned children of American soldiers, like Tam, to come to the United States.

And, the official explained, the child's immediate family could come, too.

Tam did not believe the official. He was afraid the Vietnamese government was trying to trick him. So he fled to Pleiku to find his adopted mother.

The two confirmed that the program, called the Amerasian Homecoming Act, was real.

But then his adopted mother did something surprising. She sold Tam to another family. In return, she received about 56 grams of gold.

Yet Tam's new “family” did not succeed in joining him in the United States.

At the age of 19, Tam left Vietnam alone. He was, again, all by himself.

Jannies

Jannies also came to the United States through the Amerasian Homecoming Program. But she came with her mother and a stepsister.

They were all searching for her father.

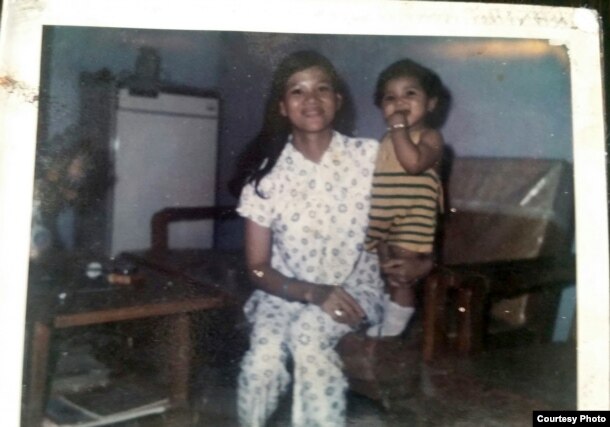

Sol was a soldier working at an American base in Tam Quang. He and Nguyen Thi Chin lived together for four years before Chin gave birth to a baby girl, named Jannies.

Four months later, Sol was ordered to withdraw from Vietnam. He promised to return for Jannies and her mother. He even sent letters and money. But when guerrilla forces entered Bien Hoa in 1972, Jannies and her mother fled.

To protect her daughter, Chin destroyed all evidence of Sol. She burned his letters and photos. She tried to straighten her daughter's curly hair. She claimed Jannie's father was a dark-skinned instead of a black American.

Eventually, Chin moved back to her parents' home in central Vietnam. They settled near Tam Quang on Highway 1. Jannies was five.

Jannies said, “I got beat up every day. They said I'm from the enemy. They said I'm not supposed to be here. And I'm not supposed to go to school.”

Others called her degrading terms for mixed race. They said her mother slept with her father for money.

These insults were common for mixed-race children. Throughout Vietnam, the children were ostracized because they looked different. People called them “bui doi,” meaning “dust of life.”

Jannies learned to deal with the insults. She did not have a choice. Then, she learned about the U.S. government's program for mixed-race children. Chin, Jannies, and a step-sister were accepted. They were invited to move to the American state of Oklahoma.

For 18 years, Jannies had been waiting for Sol to bring her to the U.S. Finally she was going. But it was the U.S. government - not her father - that was bringing her.

“This is my family”

Moki, Tan, and Jannies have these things in common: they are of mixed race, they now live in the United States, and they are all using DNA tests to search for their American families.

Moki wants to investigate her connections so she can understand her medical history. She found evidence of a genetic link to a person in Alabama who appears to be a cousin. But she has not located a closer relative. The search is painfully slow. But, for now, she is pleased that her daughter is healthy again.

Tam had a more fruitful experience. He found a close genetic match to a man from the state of Georgia named Chris Murray.

Murray is Tam's uncle. He explained that his brother, Danny, was Tam's father. Danny was based in Tuy Hoa during the Vietnam War. But he died in 1989 in an automobile accident.

Tam cried when he told the story. He said, “I've spent 43 years looking for my father. And he's no longer alive when I found him.”

Tam still wanted to recognize the connection to his American family. He changed his name to Thomas Danny Murray to honor his father and paternal grandfather.

Jannies has had the least success in discovering her American family. She still has not found Sol. But she has developed a deep relationship with the mixed-race “dust of life” community.

On a Saturday afternoon in November, Jannies was at an airport motel in Oklahoma City. Almost everyone else in the area was watching a television broadcast of an American football game.

But not Jannies.

She was rehearsing traditional Vietnamese songs with 60 other “dust of life.” They were performing that night for a fund-raiser. The money would help others who were still left behind.

Two of the Vietnamese-Americans orphans were singing. Jannies stopped to listen to the words:

“I was born fatherless.

My mother abandoned me when I was just an infant.

Nobody cares about my life.

No one shows mercy to the bi-racial child.

There is only me on my own…”

Jannies looked around her at the other abandoned children. “This is my family,” she said. “These are my brothers and sisters.”

I'm Kelly Jean Kelly.

And I'm Bryan Lynn.

Hai Do reported this story for VOANews.com. Kelly Jean Kelly adapted his report for Learning English. George Grow was the editor.

We want to hear from you. Write to us in the Comments Section.

Words in This Story

degrading - adj. without respect

ostracized - v. to be not included in a group

fruitful - adj. producing a good result

fund-raiser - n. a social event held to collect money