Researchers are now reporting a link between the weather event known as El Niño and an increase in cholera cases in eastern Africa.

This means that knowing when there is going to be an El Niño climate event might improve public health preparedness.

El Niños are a global climate phenomenon that takes place every two to seven years.

During an El Niño, the temperature of the ocean's surface, in the eastern Pacific near South America, becomes warmer than usual. The warming begins in late December.

The following year, in the fall, sea surface temperatures also warm in the western Pacific, leading to extreme weather events like flooding and droughts. These conditions also support cholera outbreaks.

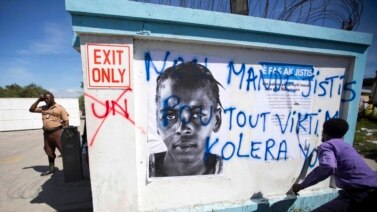

Cholera is an infectious bacterial disease that people usually get from infected water supplies. The water becomes contaminated if human waste containing the bacteria enters the water.

Finding the link

About 177 million people live in areas where the cases of cholera increase during El Niño.

However, there has been little evidence of El Niño's health effect in Africa. The recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in March found that cholera cases increased in countries in East Africa.

“Because they can either lead to surface flooding that washes contamination into drinking water in areas where there's open defecation," said epidemiologist Sean Moore who led the study. "It also can lead to overflowing of sewer systems in urban areas which again can lead to contamination of drinking water.”

Moore is an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health in Baltimore. He says there are about 150,000 cases of cholera a year, mostly in Africa south of the Saharan Desert.

Researchers measured changes in the number of cholera cases during El Niños between the years 2000 and 2014. They found cases increased by almost 50,000 in eastern Africa during El Niño years.

Scientists also saw a small increase in the number of cholera cases in areas hit by drought because of El Niño.

Moore said when water supplies decrease, available drinking water can become contaminated by bacteria in human waste.

The study also reported a surprising finding: cholera cases dropped in some parts of Africa. Researchers found there were 30,000 fewer cases reported in southern Africa during El Niño years compared to non-El Niño years. The reasons for the drop in cases is not clear at this time, Moore said.

Cholera remains a dangerous disease

Without treatment, death rates from cholera can be as high as 50 percent.

El Niño's can be predicted six to 12 months ahead of time, Moore said. That means public health officials can prepare for outbreaks, which usually happen soon after the climate event begins.

“An advance warning could, even if it doesn't prevent outbreak, it could at least prevent the deaths that tend to occur during the early part of an outbreak,” he said.

Using a treatment known as oral rehydration therapy, Moore said the risk of death from cholera drops to 1 percent. He said there are now low-cost cholera vaccines that could be used to prevent the disease if it is known that an area is going to be hit by an El Niño.

I'm Phil Dierking

Jessica Berman wrote this story for VOA News. Phil Dierking adapted it for VOA Learning English. Mario Ritter was the editor.

Do you know how to keep your drinking water safe? We want to hear from you. Write to us in the Comments Section or on our Facebook page.

Words in This Story

cholera - n. a serious disease that causes severe vomiting and diarrhea and that often results in death

contaminate - v. to make something dangerous, dirty, or impure by adding something harmful or undesirable to it

defecate - v. to pass solid waste from the body

drought - n. a long period of time during which there is very little or no rain

epidemiologist - n. the study of how disease spreads and can be controlled

phenomenon - n. something that can be observed and studied and that typically is unusual or difficult to understand or explain fully

advance - adj. before something happens