Prehistoric people may have hunted and killed other members of their own species and eaten them, but probably not for food.

That is what a new study written by James Cole of the University of Brighton in England says. Cole says compared to large animals, humans do not provide much food. His study was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Cole studied nine places where fossils have been found and where researchers have found evidence of cannibalism. Such signs include cutting marks on the bones.

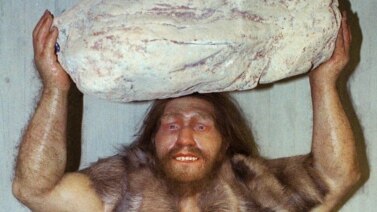

Scientists dated the sites to between 14,000 and more than 900,000 years ago. That is the so-called Paleolithic period, also known as the Stone Age.

Five of the sites had Neanderthal fossils, the remains of earlier human ancestors. Two sites had fossils of prehistoric members of our own species and the others had fossils from much earlier human ancestors.

Cole estimated how many calories each of the bodies at each site had. He used earlier studies that found eating an average-sized modern-day human could provide up to 144,000 calories. He then made his estimates, based on the ages of the bodies at the sites.

The researcher found that the hunters would not get as much energy from the humans as they would from one large animal -- like a mammoth, a woolly rhino or a bear. So, Cole asked, why would the early humans hunt and kill their own species?

“You're dealing with an animal that is as smart as you are, as resourceful as you are, and can fight back in the way you fight them,” Cole noted.

He says our ancestors may have eaten members of their species who had died because they did not have to be hunted. But he says cannibalism probably took place for reasons other than the need for food. He said it could have happened after times of violence or to defend territory.

Tim White of the University of California, Berkeley and Paola Villa of the University of Colorado Museum in Boulder said they do not know any scientists who believe our ancestors hunted each other for food. In an email, Villa said the new study “does not change our general understanding of human cannibalism.”

But Palmira Saladie, of the Catalan Institute for Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution near Barcelona, Spain, said Cole's study “will undoubtedly be key in the interpretation of new sites (and) the reevaluation of old interpretations.”

In an email, she wrote that, to understand why our ancestors sometimes ate each other, “we still have a long way to go.”

I'm Dorothy Gundy.

The Associated Press news agency reported this story. Christopher Jones-Cruise adapted the report for Learning English. Mario Ritter was the editor.

We want to hear from you. Write to us in the Comments Section, or visit our Facebook page.

Words in This Story

fossil - n. something (such as a leaf, skeleton, or footprint) that is from a plant or animal which lived in ancient times and that you can see in some rocks

cannibal - n. a person who eats the flesh of human beings

date - v. to show or find out when (something) was made or produced

Paleolithic - adj. of or relating to the time during the early Stone Age when people made rough tools and weapons out of stone

calorie - n. a unit of heat used to indicate the amount of energy that foods will produce in the human body

resourceful - adj. able to deal well with new or difficult situations and to find solutions to problems

key - adj. extremely important

interpretation - n. the act or result of explaining or interpreting something; the way something is explained or understood

reevaluate - v. to judge the value or condition of (someone or something) again