DOUG JOHNSON: Welcome to AMERICAN MOSAIC in VOA Special English.

(MUSIC)

I'm Doug Johnson. This week, our program is all about the Civil War -- in a new film and museum shows, and music from the new band the Civil Wars.

(MUSIC)

"The Conspirator"

DOUG JOHNSON: The United States is holding events in remembrance of the one hundred fiftieth anniversary of the start of the Civil War. And Hollywood also is taking a look. A new film from director Robert Redford explores the plot that resulted in the murder of President Abraham Lincoln. Mario Ritter has more.

MARIO RITTER: On April fourteenth, eighteen sixty-five, a gunshot is fired at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, DC. The bullet hits President Abraham Lincoln. He dies within hours.

The shooter is John Wilkes Boothe, an actor. He is angry about the freeing of slaves and the South’s loss in the Civil War. But John Wilkes Booth did not carry out the assassination alone.

The new film, “The Conspirator,” tells the story many Americans do not know about. The action surrounds the military trial of Mary Surratt, one of the accused plotters, and the mother of another.

MARY SURRATT: “I am a Southerner and a devoted mother. But, I am no assassin.”

Robin Wright plays Mary Surratt. She says the movie is about more than facts.

ROBIN WRIGHT: “It’s about humanity. It’s not so much about historical evidence. It’s a real piece about human behavior.”

Mary Surratt was a businesswoman in the eighteen sixties. She operated a boarding house, a home where visitors stayed. Her boarding house, however, was also used by her son and several other people as a meeting place to plot the murder of the president. All the plotters have been arrested except her son, who has disappeared.

A lawyer named Frederick Aiken decides to defend Mary Surratt. He does not necessarily think she is innocent. But he hopes to make sure she gets a fair trial. James McAvoy is Aiken.

FREDERICK AIKEN: “Mary you have to tell us where your son is.”

MARY SURRATT: “Us? I’m have to tell us?...Whose side are you on.”

FREDERICK AIKEN: “I’m trying to defend you.”

MARY SURRATT: “By suggesting I trade my son for myself?”

Historian Fred Borch was an expert adviser to the filmmakers.

FRED BORCH: “What I think the movie is trying to do is to show you that guilt or innocence aside, she didn’t get a fair trial and neither did the others because the government was so afraid that if they didn’t stomp on this conspiracy, that there might be more attacks by the Confederates coming.”

The first showing of “The Conspirator” was to a group gathered at the same theater where President Lincoln was killed. Director Robert Redford says he hopes the movie will make people think of the assassination in a new way.

ROBERT REDFORD: “I’ve never deluded myself into thinking that films change anybody’s opinion, or has an impact that’s going to change policy or anything like that, but I would think that being aware of what happened and seeing how that process has repeated itself, might strike a chord. I would hope so."

(MUSIC)

Civil War Exhibits

DOUG JOHNSON: One hundred fifty years ago today, President Abraham Lincoln approved an order for the services of seventy-five thousand militiamen. It was just a little over a month since he had taken office. And it was three days after the Confederate Army of the southern states attacked federal forces at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. The American Civil War had begun.

Slave John Washington wrote about the situation in his hometown of Fredericksburg, Virginia:

“The war was getting hotter every day. The town was now filled with rebel soldiers and their outrages and dastardly acts toward the colored people can not be told. It became dangerous to be out at night. The whites was hastening their slaves off to safer places of refuge. A great many slave men were sent into the rebel army as drivers, cooks, hostlers and anything else they could do.”

John Washington was among almost thirteen hundred slaves in Fredericksburg. There were about four hundred twenty free blacks and more than thirty-three hundred whites.

The stories of many of these men and women and their experiences during the Civil War can be found at the Fredericksburg Area Museum and Cultural Center. The stories are part of a permanent exhibit called “Fredericksburg at War” and in another show called “Letters and Diaries of the Civil War.” That show continues through July.

Sara Poore is the director of education and public programs at the museum. On Tuesday, she led about thirty eighth-graders from a school in North Carolina on their visit to the Civil War exhibits.

She told them how it was that slave John Washington could write his memoirs.

SARA POORE: “It was against the law to teach your slaves to read and write unless it had something to do with religion. Then you could teach them to read the Bible. John Washington’s mother taught him to read and write when he was a young boy.”

On April eighteenth, eighteen sixty-two, Union soldiers started moving into Fredericksburg. Sarah Poore describes what happened.

SARA POORE: “They could be seen across the river, the Rappahannock River. John Washington recorded that moment. He said ‘the glistening bayonets of the Union Army can be seen. I am sure of my freedom now. All the white people are in the streets scared. All the manservants are on the rooftops joyous that freedom in near.”

Then Sarah Poore gives the students more to think about with words from a white Fredericksburg resident, Maureen Breckenridge.

SARA POORE: “She wrote in her diary: ‘The union solders are near. We will be destroyed. They will take our land, they will take our property. We are all full of fear.’ Two very different perspectives of the exact same event.”

Sara Poore told the students to remember these different images as they went through the exhibit. She said the military action of the Civil War is very important. But she said the experiences of civilians affected by the conflict were central to understanding the period in American history.

During the Union occupation of Fredericksburg, thousands of escaped slaves fled through Virginia on their way North.

WW Wright was an engineer and superintendent of military railroads at the time. He wrote about the fleeing slaves in an official military document.

READER: “During the last two days the contrabands fairly swarmed about the Fredericksburg and Falmouth Stations, and there was a continuous black line of men, women and children moving north along the road, carrying all their worldly goods on their heads. Every train running to Aquia was crowded with them.

"They all seemed to have perfect confidence that if they could only get within our lines they would be taken care of somehow. I think it is safe to estimate the number of contrabands that have passed by this route since we took possession of the road at ten thousand."

John Washington was among the fleeing slaves. In a recording at the Fredericksburg Museum and Cultural Center, an actor reads from Washington’s life story.

SOUND: “A most memorable night was the soldiers assured me that I was a free man. Before morning I had began to feel like I had truly escaped from the hands of the slave master. And with the help of God I would never be a slave no more. I felt for the first time in my life that I could now claim every cent that I should work for as my own. Life had a new joy awaiting me.”

We talked with Sara Poore about visitors’ reactions to the Civil War exhibits. She said what surprises them most is when she states firmly that the Civil War was, in fact, about the fight over slavery. She says states rights, economic and social inequalities between the South and North and other issues were debated. But Sara Poore says major historical documents clearly show that slavery was the central issue of dispute.

(MUSIC)

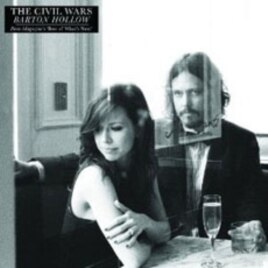

"Barton Hollow" by the Civil Wars

DOUG JOHNSON: Musicians Joy Williams and John Paul White are the Civil Wars. Their first album, “Barton Hollow,” is number two on Billboard Magazine’s Folk Rock chart. One newspaper calls the musical connection between Williams and White “seriously joyful.” Katherine Cole has more.

(MUSIC)

KATHERINE COLE: That is “Twenty Years,” the first song on the Civil Wars’ first album, “Barton Hollow.”

Joy Williams and Paul John White have known each other for only a few years. They met on a music writing project in Los Angeles.

On the Civil Wars’ website, Paul John White says his connection with Joy Williams was immediate. It was, he says, “like we’d been in a family band or something for most of our lives.”

Joy Williams had been singing Christian music until she met White. She told the Los Angeles Times newspaper that she has found new creative freedom working with him. She says now she knows she can write about any subject.

“My Father’s Father” is a moving song about a return to one’s roots.

(MUSIC)

John Paul Williams comes from Alabama. Joy Williams is a native Californian. Now, the two live and work in the home of country music, Nashville, Tennessee.

We leave you with, “I’ve Got a Friend,” from the Civil Wars album, “Barton Hollow.”

(MUSIC)

DOUG JOHNSON: I’m Doug Johnson. Our program was written by Julie Taboh and Caty Weaver, who was also the producer.

Join us again next week for music and more on AMERICAN MOSAIC in VOA Special English.

(MUSIC)