DOUG JOHNSON: Welcome to American Mosaic in VOA Special English.

(MUSIC)

I’m Doug Johnson.

Today on our show we listen to the great singer Lena Horne, who died this week at age ninety-two…

And we answer a question about the inventor of the telephone.

But first we report on places people are gathering to share food, drink and science.

(MUSIC)

Science Cafes

DOUG JOHNSON: Many people have difficulty understanding complex subjects in science. And scientists often have trouble explaining what they do in language that the public can understand. Now there is a movement to bring scientists out of the laboratory and into the community for talks over dinner and drinks. Shirley Griffith has more.

JULIE BIERACH: "Hello everyone. Welcome to Science Cafe. Thank you so much for coming out tonight."

SHIRLEY GRIFFITH: Most people learn about science in school, from the media or on the Internet. But at a science cafe, they get to learn about it from the scientists themselves. There are now more than one hundred science cafes at bars and restaurants in the United States.

For the past four years, Al Wiman has organized a monthly science cafe for the Saint Louis Science Center in Missouri. Mister Wiman says the idea started in Europe. It is a way to get scientists to talk with the general public about what they do. He says part of what makes the science cafe successful is that the conversations take place at a restaurant called Herbie's.

Saint Louis has two science cafes. The second one is called Science on Tap. Washington University professors talk about their research. Science on Tap meets once a month at a bar called the Schlafly Bottleworks. Many different people attend the events. They include engineers, doctors, students and other people interested in science. So what brings people out to a bar to talk about science?

MIKE STUART: "I like the atmosphere. It's fun to learn things and enjoy a good beer.

RON ROGERS: "I would call this a civilized education."

ROBERT PLESS: "Why aren't more science talks in a bar, right? Like this is the place where you learn and you ask and you understand things most quickly, instead of a lecture where it's really just a one-way thing."

Scientists talk about many kinds of subjects -- from black holes to biological clocks to botany. But the evening really gets interesting after the scientist's talk ends and the audience gets to ask questions. Sometimes the questions go on longer than the talk itself. But the scientists do not seem to mind. Ivan Jimenez of the Missouri Botanical Garden says he likes the chance to talk about his work with people outside the scientific community.

(MUSIC)

Alexander Graham Bell

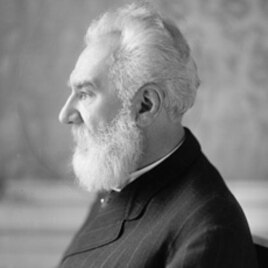

Out listener question this week comes from Vietnam. Le Thuy Kieu wants to know about Alexander Graham Bell.

The inventor was born in Edinburgh, Scotland in eighteen forty-seven. From an early age, Aleck liked to make new things and find new ways of doing work. He was also interested in art, poetry and music. He taught himself how to play the piano.

His mother’s increasing deafness led the young man to study acoustics -- the way we hear and how sounds are made. He also found a way to help his mother hear better. Instead of speaking into her ear, he spoke toward the top of her face. He also carefully formed the words he spoke.

Alexander Graham Bell believed one day machines would be invented to help deaf people hear and speak. He did not like the idea of sign language. For most of his life, Bell worked with deaf people. In eighteen seventy, the family moved to Canada. The next year Bell moved to Boston, Massachusetts, to teach at a school for the deaf.

Bell had begun experimenting with electricity and sound when he was eighteen years old. At that time he invented what he called his “harmonic telegraph.” This electrical machine could send and receive “beeps” and other sounds over a wire.

But it was not until March tenth, eighteen seventy-six that Bell was able to send the human voice over a wire. That moment is famous. Alexander Graham Bell was in one room. His assistant, Thomas Watson, was in another. The inventor said into the device, “Mister Watson, come here. I want to see you.” Watson heard him clearly. The telephone was born. Bell was twenty-nine years old.

Bell Telephone Company made Alexander Graham Bell a rich man. But he spent his whole life continuing to study and invent. Bell experimented with devices that could find bullets and other metal in the body. He developed a machine to aid breathing. He was also interested in vehicles that could move in air and on water. Alexander Graham Bell died in Nova Scotia, Canada, in nineteen twenty-two. He was seventy-five.

(MUSIC)

Lena Horne

DOUG JOHNSON: Celebrated performer Lena Horne died Sunday at a hospital in New York City. The singing star broke racial barriers in movies and live theater. In the nineteen forties, she was the first black woman to sign a long-term agreement with a major Hollywood movie studio. The deal included a famous agreement. It said she would never have to play a maid.

Faith Lapidus has more on Lena Horne, her music and her rich life.

FAITH LAPIDUS: Lena Horne was born in nineteen seventeen in Brooklyn, New York. She was the great-granddaughter of a freed slave. Her mother was an actress. Lena’s grandmother helped raise her. Her grandmother was a social worker and an activist for women’s voting rights.

At sixteen, Lena began dancing and singing in the famous Cotton Club in the Harlem area of New York. A few years later she went to Hollywood. She starred in an African-American musical film called “Stormy Weather” in nineteen forty-three. “Stormy Weather” also became Lena Horne’s best known song.

(MUSIC)

Lena Horne also made movies with white actors in the nineteen forties. She always played a nightclub singer. And she was always filmed so that her part could be cut out for versions shown in the American South. Racial separation laws were still in place in the South at the time.

Lena Horne said the experience and other discrimination led to her work in the civil rights movement.

LENA HORNE: “When I went to the South and met the kind of people who were fighting in such an unglamorous fashion, I mean, fighting to just get someplace to sit and get a sandwich. I felt close to that kind of thing because I had denied it and had been left away from it so long. And I began to feel such pain again.”

Lena Horne had a rich, raw, deep voice that was famous for blues singing. But she was skilled in many styles. Here she adds a Latin beat to the song “Night and Day.”

(MUSIC)

In nineteen eighty-one, she opened her one-woman show on Broadway in New York. It was called “Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music.” It ran for three years. She won a Tony award, two Grammys and other honors.

Lena Horne was ninety-two when she died. We leave you with her performing “What’ll I Do.”

(MUSIC)

DOUG JOHNSON: I'm Doug Johnson. Our program was written by Shelley Gollust, with reporting by Veronique la Capra, Jim Tedder and Caty Weaver who was also the producer.

You can find transcripts, MP3s and podcasts of our shows at voaspecialenglish.com. You can also follow us on Facebook, Twitter and iTunes at VOA Learning English.

Join us again next week for AMERICAN MOSAIC, VOA’s radio magazine in Special English.

(MUSIC)