Hello, and welcome back to As It Is from VOA Learning English.

I’m Christopher Cruise in Washington.

Today on the program, we go to South Africa, where conservationists are using poison to save rhinos…

“It is a little bit sore, but hard sore, but I’m, I’m happy in the fact that I now know that she is potentially very, very safe.”

Then, we go to Kenya, where wildlife officers are using high-tech methods to protect rhinos from poachers.

But first, we take you to Uganda, where hunters and farmers are threatening the country’s remaining lion population…

“If nothing is done and the population keeps going down, then it will not be likely that we will have them.”

Lions, and rhinos -- the subjects of our conversation today, as you learn everyday American English on As It Is, from VOA.

Can Uganda’s Lions Survive Poachers and Farmers?

Uganda’s lion population has fallen by 30 percent in the last ten years. Experts are warning that the big cats could soon disappear from the country. As Caty Weaver reports, that could hurt Uganda’s important and profitable tourism industry.

We are in one of Uganda’s national parks. There are grasslands as far as the eye can see. And there are many travelers from around the world. They have woken up early -- before the sun rises -- and their camps are now empty.

They are hunting, not with guns but with cameras.

Jossy Muhangi works for the Uganda Wildlife Authority. He knows what the tourists seek.

“For most of our game drives, people want to wake up at 6 a.m., in the wee hours, and they really look. Their first choice or the favorite animals for the tourists -- be it local or international -- would be a lion. For every tourist who comes to Uganda, the dream would be to at least spot a lion.”

Lions are growing harder to find throughout Uganda. Last month, the non-profit organization Wildlife Conservation Society said now only a little more than 400 lions remain in Uganda. That is one third less than ten years ago.

Tutilo Mudumba is a researcher with the Wildlife Conservation Society, or WCS. He says lions face many threats.

“You may find illegal poaching using, for example, air snares, taking place in Murchison Falls National Park. You may have a problem of competition for grazing land between lion prey and cattle, and then you have sometimes poisoning, we suspect to clear the area of predators so that they can use it for grazing.”

Mr. Mudumba says if no action is taken to reduce these threats, lions could one day disappear from Uganda.

“If nothing is done and the population keeps going down, then it will not be likely that we will have them. If they reduce by 30 percent every 10 years, then of course those are the number of years left for you to have zero.”

The disappearance of lions from Uganda could hurt the country’s economy. In 2006, the WCS studied the expectations and spending of visitors to Uganda. It found that each lion was worth $13,500 a year to the economy. The study also found that only 60 percent of tourists would still visit Uganda’s national parks if there were no lions left. The World Bank estimates tourism brought 1 billion dollars to Uganda’s economy last year.

I’m Caty Weaver.

Using Poison to Save Rhinos in South Africa

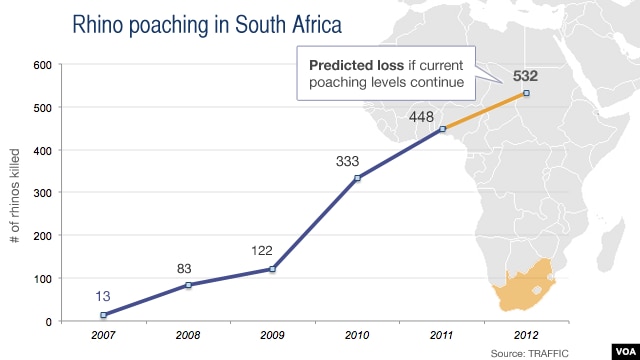

The illegal hunting, or poaching, of rhinoceroses has increased in recent years in South Africa -- where most of the world’s rhinos live.

Almost 800 rhinos have been poached in South Africa so far this year. That is more than three percent of the country’s rhino population.

Rhinos are killed for their horns. These can be illegally sold for tens of thousands of dollars in Asia. The horn is used in traditional Chinese medicine. The rhinos’ eyes and tail are sometimes used in other traditional activities.

Graham Shipway runs a business in the Plumari Africa Game Reserve near Johannesburg. He found at least two dead rhinos last month.

“This is a female rhino, pregnant, 23 years old. Last Saturday she was poached. You can see over here the bullet hole. It’s a through and through, which means it’s a heavy caliber bullet. They hacked off her horn, as you can see here. They gouged out her eyes, as you can see. And they cut off her tail -- all for two kilograms of horn.”

The government and private game reserves are trying different ways to fight poachers -- including armed patrols. They are also cutting off rhinos’ horns, and even poisoning the horns. This makes them worthless on the black market. Several hundred rhino horns have been injected with poison so far this year. Officials hope the poisoning will help save rhinos from extinction.

The rhino is injected with a drug that paralyzes the animal but does not make them unconscious. Then, a hole is drilled into its horn. A poison that is dyed red is then put into the hole. Conservationist Lorinda Hern says the poison is safe for rhinos, but harmful to humans. They can suffer from vomiting, diarrhea and nerve damage. In some cases, the poison can kill a person.

“If you buy a horn and it’s this kind of color you obviously know that it’s been tampered with and that it’s not safe for human consumption. So, yeah, 60,000 U.S. dollars per kilo versus zero.”

Once the poison is placed in the rhino’s horn, the rhino wakes up, unharmed.

“It’s a little bit sore, but hard sore, but I’m, I’m happy in the fact that I now know that she is potentially very, very safe.”

Conservationists hope to save hundreds of rhinos each year by making their horns worthless to poachers.

Using High-Tech Devices to Save Rhinos in Kenya

Wildlife officials in Kenya for the first time are using high-tech efforts to fight rhino poaching. They are placing small devices into the rhinos, called transponders. The transponders let officials follow the animal and even the horn if it is cut off. Using the transponders is necessary to fight the increasing poaching of rhinos in Kenya.

The country’s chief law official said poachers have killed 90 elephants and 35 rhinos this year.

Last month, the Kenya Wildlife Service used a helicopter to gather rhinos in an area of Nakuru National Park. A team of rangers shot the rhinos with drugs to make them sleep. They then put four transponders into each rhino -- one in the front horn, another in the smaller rear horn as well as one each in the neck and the tail.

The transponders were donated to the Kenya Wildlife Service by the World Wildlife Fund.

And that’s our program for today.

I’m Christopher Cruise reporting from VOA Learning English headquarters in Washington.