This is IN THE NEWS in VOA Special English.

Moammar Gadhafi came to power in Libya on September first, nineteen sixty-nine. He led a military overthrow while King Idris was away. Early relations with the United States were generally good, says Bruce St John, the author of seven books on Libya.

BRUCE ST JOHN: “In the early years, he was very much focused on Arab nationalism, Arab unity, Arab socialism. And in fact, the United States government in the first two or three years -- maybe even until nineteen seventy-four -- there were people in the United States government who thought we could work with the man and work with his regime. It was only later that he began to employ terrorist-type techniques, not only in North Africa and the Middle East, but eventually throughout the world.”

Colonel Gadhafi distrusted his own generals, so over the years he built up special brigades. He built these forces with his sons and members of the military loyal to his native tribe and its allies. He also brought in foreign forces -- African mercenaries.

During the nineteen seventies, he tried to unite Libya with other Arab countries. Experts say that was also when he began to provide aid to what some governments considered terrorist organizations. These included the Irish Republican Army and the Abu Nidal Group.

Relations with the United States fell to an all-time low during the eighties when Ronald Reagan was president. He called Colonel Gadhafi "the mad dog of the Middle East."

Author Bruce St John points to two events from that time. In December of nineteen eighty-five, terrorists attacked the Rome and Vienna airports. And in April of nineteen eighty-six, a bomb exploded at a West Berlin discotheque popular with American troops. Two soldiers died.

BRUCE ST JOHN: “Gadhafi and his regime -- the evidence was somewhat murky -- but the United States government believed that they were involved in both of those instances. And it was particularly the La Belle discotheque incident that led the Reagan administration to take a decision to punish the Gadhafi regime and put it on notice that we no longer tolerate that kind of activity.”

American planes attacked targets in Benghazi and Tripoli. Many people were killed, including the adopted daughter of Colonel Gadhafi.

In nineteen eighty-eight, a bomb blew up Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland. Two hundred seventy people died, including many Americans. Another bombing took place the following year on a French plane over Niger.

Libya refused to surrender suspects in the two bombings. Libya faced years of United Nations sanctions until it finally surrendered the two suspects in the Lockerbie bombing.

One of them, Abdel Baset al-Megrahi, was found guilty. But Scotland released him in two thousand nine, saying he was dying of prostate cancer. He is still alive.

In two thousand three -- the year of the American-led invasion of Iraq -- Moammar Gadhafi became more cooperative with Western countries. He agreed to pay the final amount of money owed to families of the Lockerbie bombing victims. And he announced that Libya was ending its programs to make weapons of mass destruction.

The United States reopened diplomatic relations with Libya in two thousand six, but waited three more years to send an ambassador.

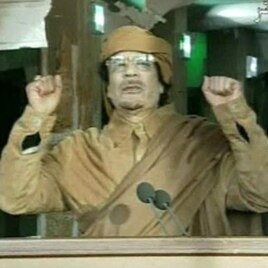

The uprising in Libya began last week in the east. Colonel Gadhafi, in a speech Monday, noted China's use of tanks against pro-democracy demonstrators in nineteen eighty-nine. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, died. In his words: "The unity of China was more important than those people on Tiananmen Square."

Reporting on the unrest in the Middle East and North Africa has been limited in China. Workers put construction barriers around a site in Beijing where an online campaign has been urging weekly protests on Sunday afternoons.

And that's IN THE NEWS in VOA Special English. For more news, go to voaspecialenglish.com. I'm Steve Ember.

Contributing: Elizabeth Arrott, Stephanie Ho, Andre de Nesnera and Edward Yeranian