Memorial Day honors all of those who have died in America's wars. But the holiday began as a way to remember soldiers killed in the Civil War. On May 30th, 1868, flowers were placed on the graves of Union and Confederate soldiers at Arlington National Cemetery.

Lines of simple white headstones mark the graves. The 80-hectare cemetery also serves as a burial place for people of national and historical importance.

The cemetery is in Arlington, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington. Next to the burial ground is the Defense Department headquarters at the Pentagon.

A funeral with full military honors traditionally includes a caisson to transport the body. A caisson is a wagon pulled by horses. At Arlington, six black or gray horses pull caissons made in nineteen eighteen. A seventh horse carries the leader of the procession.

Sometimes a horse without a rider also takes part in a funeral. The best known riderless horse was Black Jack. He took part in the funerals of presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. The horse was named after a famous general known as “Black Jack” Pershing.

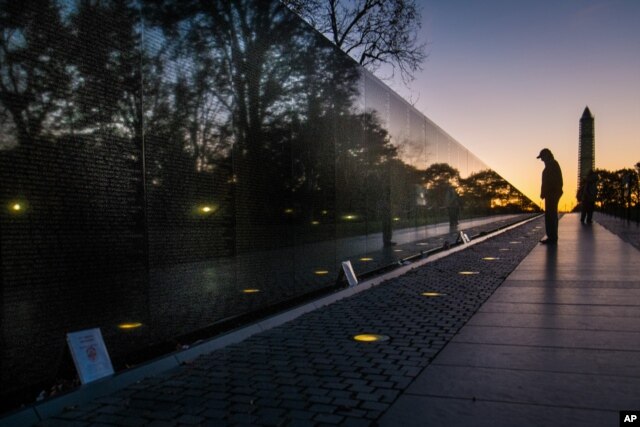

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial is perhaps the best-known memorial in America’s capital.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial was the idea of a former soldier named Jan Scruggs. He fought in the Vietnam War. The war ended in 1975. Many soldiers came home only to face the anger of Americans who opposed the war.

Jan Scruggs organized an effort to remember those who never returned.

In 1980, a group of former soldiers announced a competition to design a memorial. The winner, Maya Lin, was 21-years-old. She was studying architecture at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Maya Lin designed a memorial formed by two walls of black stone.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial opened in 1982.

The walls are about 76 meters long. They are set into the earth. They meet to form a wide V. The names of more than 58,000 Americans killed or declared missing-in-action are cut into the stone.

Nearby is a statue of three soldiers. They are looking in the direction of the names. Another statue honors the service of women in the war.

Almost any time of day, you can see people looking for the name of a family member or friend who died in the war. Once they find the name, many rub a pencil on paper over the letters to copy it.

Many people leave remembrances at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. One day, as crowds passed by, two young men left notes. A woman in her late 70s or 80s left a handful of red roses.

After the success of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Congress approved a memorial to Korean War veterans. The Korean War Veterans Memorial opened in July of 1995. It is near the Vietnam memorial.

The Korean War lasted from 1950 to 1953. The memorial honors those who died. It also honors those who survived.

The Korean War has been called the last foot soldier's war. The memorial includes a group of 19 statues of soldiers. The soldiers appear to be walking up a hill, toward an American flag.

Artist Frank Gaylord made the statues from steel. Each is more than two meters tall. People who drive along a road near the memorial sometimes think the statues are real soldiers.

On one side of the Korean War Veterans Memorial is a stone walkway. It lists the names of the 22 countries that sent troops to Korea under United Nations command. On the other side is a shiny stone wall. Sandblasted into the wall are images from photographs of more than 2,500 support troops.

A Pool of Remembrance shows the numbers of American and United Nations forces killed, wounded, captured or missing. The total is more than two million. Cut into the wall above the pool is a message: "Freedom is Not Free."

One of the lesser known memorials on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., is often called "the temple." The round stone structure honors people from the District of Columbia who died in World War One.

The war was fought from 1914 to 1918. The memorial was completed in 1931. It is the only District of Columbia memorial on the National Mall.

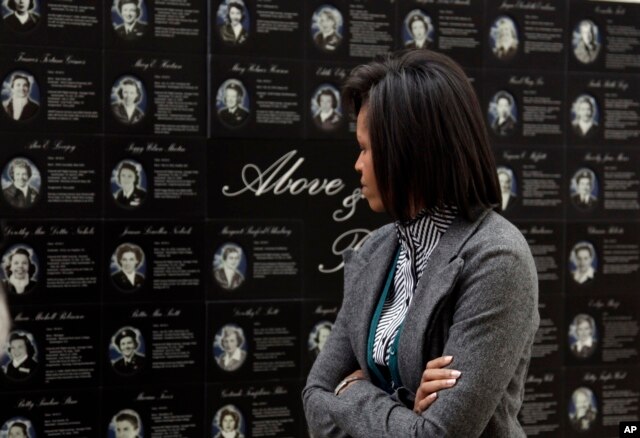

In 1986, President Ronald Reagan signed legislation to honor women in the military. The Women in Military Service for America Memorial opened in 1997.

The memorial is near the entrance to Arlington National Cemetery. It recognizes the service of all the women who have taken part in the nation's wars. About two million women have served or currently serve in the armed forces.

Michael Manfredi and Marion Gail Weiss designed a place of glass, water and light. The memorial has a large wall shaped in a half-circle. In front, 200 jets of water meet in a pool.

Inside the memorial, the stories of women in wartime are cut into glass panels. Computer records contain the names, pictures, service records and personal statements of about 250,000 military women.

The World War Two Memorial rises between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument on the National Mall. America entered the war after Japan bombed the Navy base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7th, 1941.

Sixteen million men and women served in the American military between 1941 and 1945. More than 400,000 died.

The World War Two Memorial stands in the open air. It is built of bronze and granite. In the center, at ground level, is a round pool of water. Except in very cold weather, water shoots from a circle of fountains in the middle.

When the sun is just right, rainbows of color dance in the air. Fifty-six stone pillars rise around the pool. These represent each of the American states and territories, plus the District of Columbia, at the time of the war. On two tall arches appear the names of where the fighting took place. One says Atlantic; the other says Pacific.

Many visitors to the memorial served during the war. One visitor, a former Navy man, once said: "The only good thing about my fighting in the war was that I was too young to be terrified."

A federal law passed in 2000 calls on Americans to stop for one minute at three o'clock local time on Memorial Day. The National Moment of Remembrance honors the members of the armed forces and others who have died in service to America.

(This story is written by Jerilyn Watson and edited by George Grow)