BARBARA KLEIN: Welcome to THIS IS AMERICA in VOA Special English. I’m Barbara Klein.

STEVE EMBER: And I’m Steve Ember. This week on our program, our subject is law and society. We hear about a new film that tells the story of a couple who helped make interracial marriage legal in America. And we hear about a new book that tells lawyers and law students what they can learn from Shakespeare.

(MUSIC)

BARBARA KLEIN: William Shakespeare died almost four centuries ago in sixteen sixteen. Yet the great English writer's understanding of human nature is timeless.

Kenji Yoshino is a professor of constitutional law at New York University. Professor Yoshino has written a book called "A Thousand Times More Fair: What Shakespeare's Plays Teach Us About Justice."

For example, take the play "Measure for Measure." There are two officials who represent opposite ideas about enforcing the law. Professor Yoshino says one of them is driven by mercy and empathy, the ability to understand another person's feelings.

KENJI YOSHINO: "That notion of judging is represented by the Duke Vicentio at the beginning of the play. And what Vicentio’s problem is that’s he’s so merciful that the state sinks into anarchy."

STEVE EMBER: The other official, Lord Angelo, is a judge who takes over for Vicentio. Lord Angelo enforces the law without any mercy. By the end, says Kenji Yoshino, both approaches are shown to be wrong.

KENJI YOSHINO: "And I want to say, look, Shakespeare got there first and he eliminated both of these extremes. He showed that the first extreme is dangerous because it lead to too much mercy. Mercy in an individual is a wonderful thing, but mercy on the part of a government actor can be a very dangerous thing."

But the professor says Shakespeare also understood that strict enforcement of the law can be unjust.

KENJI YOSHINO: "So what we’re looking for is jurists who are able to balance the claims of empathy against the claims of the rule of law and can find that middle path."

The debate over judges and empathy played a part in the Senate confirmation process for Sonia Sotomayor. She became the first Hispanic justice on the United States Supreme Court in two thousand nine. This was what she said at her confirmation hearing.

SONIA SOTOMAYOR: "We're not robots, to listen to evidence and don’t have feelings. We have to recognize those feelings and put them aside."

BARBARA KLEIN: Shakespeare dealt with questions of justice in many of his plays. Kenji Yoshino points out that in the England of Shakespeare's time, the modern state and the rule of law were evolving.

In "Othello," lago convinces Othello that his wife has been unfaithful to him. The evidence is that his wife no longer has the cloth handkerchief that Othello gave her as a symbol of his love. In fact, lago had asked his own wife to steal the handkerchief. Othello does not know that.

OTHELLO:

Villian, be sure thou prove my love a whore;

Be sure of it; give me the ocular proof:

Or by the worth of man’s eternal soul,

Thou hadst been better have been born a dog

Than answer my waked wrath!"

STEVE EMBER: Professor Yoshino explains.

KENJI YOSHINO: "Shakespeare calls this a problem of ocular proof, the idea that we need to see evidence before we believe in it -- and that, oftentimes, when metaphysical questions of guilt or innocence are difficult for us to answer, we have a tendency to reduce them to questions that pertain to physical evidence. So when we can’t measure what’s important, we make important what we can measure."

The law professor sees an example of this in the murder trial of O.J. Simpson in nineteen ninety-five. The former football star was accused of killing his ex-wife and a male friend of hers in Los Angeles.

Many people believed that the case against him was strong. But his lawyer Johnnie Cochran showed the jury a glove found at the crime scene. He showed that the glove appeared not to fit Mr. Simpson’s hand, and he told the jury again and again:

JOHNNIE COCHRAN: "If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit."

Several members of the jury said the glove influenced their decision to find O.J. Simpson not guilty of the criminal charges. A jury in a civil court, however, did later find him responsible for money damages in a case brought by family members of the victims.

BARBARA KLEIN: Professor Yoshino says the Shakespeare play that deals most directly with the law is "The Merchant of Venice." In this story, a trial takes place to decide if the moneylender Shylock can take a pound of flesh from a borrower who fails to repay his loan.

The court must decide if the contract can be enforced even though it could result in the death of the borrower, Antonio. In the end, Antonio is saved by Balthazar. Balthazar is a young lawyer who is really Portia, a woman, and who has this to say about mercy.

BALTHAZAR (PORTIA):

"The quality of mercy is not strain’d

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath; it is twice blest;"

STEVE EMBER: Law professor and author Kenji Yoshino says his students benefit from reading Shakespeare.

KENJI YOSHINO: "Law students continuously surprise me in their capacity to respond to the humanities, and when I teach my courses in law and literature, it is really as a healing or a recuperative experience both for the students and for me, because I think that what a legal education does, to paraphrase another author, is that is sharpens the mind by narrowing it."

This narrowing of the mind can help law students recognize important facts. But literature can help them understand human conflict, and he says no one has more insight into that than William Shakespeare.

(MUSIC)

BARBARA KLEIN: President Barack Obama's Kenyan father and American mother were married in Hawaii in nineteen sixty-one. At that time mixed-race marriage was still illegal in a number of states. But six years later, in nineteen sixty-seven, the Supreme Court struck down the last of these laws.

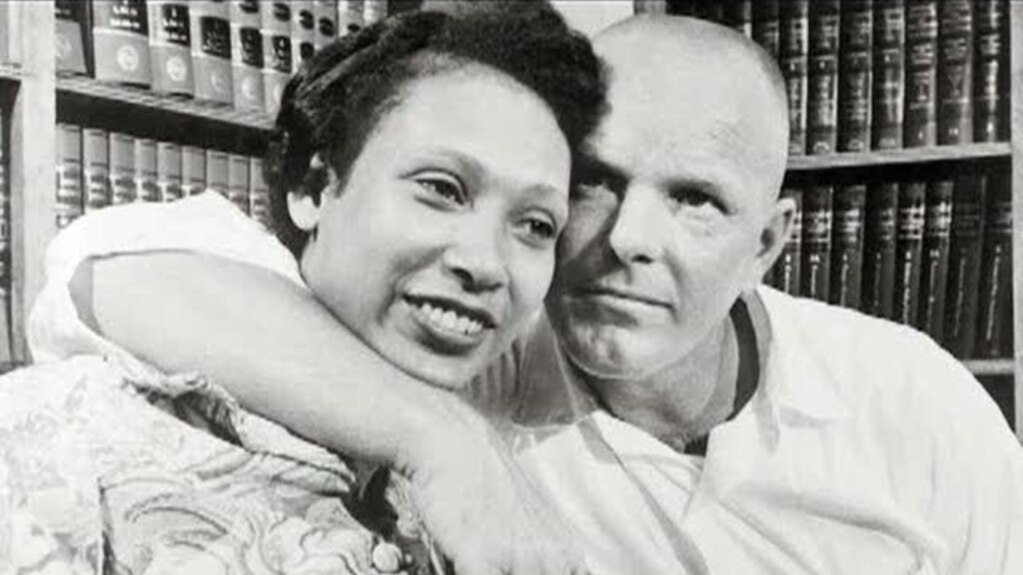

The case that led to that historic decision was brought by an interracial couple, Richard and Mildred Loving. Their story is the subject of a new documentary called "The Loving Story."

The film was shown at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York and will air on the HBO channel next February.

STEVE EMBER: The story of the Lovings is little known compared to other historic civil rights cases.

Richard Loving and Mildred Jeter met in nineteen fifty-one. At the time, Mildred was eleven years old and Richard was seventeen. He was white; she was of African and Native American ancestry. They grew up in the same Virginia town of Central Point.

Mildred later recalled what it was like living with racial segregation.

MILDRED LOVING: "The whites and colored went to school differently. Things like that, you know. You couldn't go in the same restaurants. I knew that. But I didn’t realize how bad it was until we got married."

BARBARA KLEIN: In nineteen fifty-eight, when Mildred was eighteen, she became pregnant. Virginia law barred interracial marriage. So the couple got married in nearby Washington, DC.

Mildred recalled how six weeks later, police broke down the door of their small house in Central Point and arrested them.

MILDRED LOVING: "I guess it was about two a.m. And I saw this light, and I woke up, and it was the police standing beside the bed, and he told us to get up, that we was under arrest."

(SOUND)

STEVE EMBER: The Lovings were jailed and charged with violating Virginia's anti-miscegenation laws. As their sentence, they were ordered to leave the state for twenty-five years.

They moved to Washington and had three children. But Mildred was so unhappy that, in nineteen sixty-three she wrote to the United States attorney general, Robert Kennedy.

She asked if new civil rights laws would help. He told her to contact the American Civil Liberties Union. Two young lawyers, Bernard Cohen and Philip Hirschkop, took the case.

In "The Loving Story." Mr. Cohen explains what they faced.

BERNARD COHEN: "Challenging the anti-miscegenation laws was the most serious threat to the white racists, and even those whites who were not racist but were very pro-establishment. I looked at it as an unbelievable challenge for a lawyer one or two years out of law school, to be getting involved in what was sure to be a major civil rights case."

STEVE EMBER: Nancy Buirski from North Carolina directed and produced "The Loving Story." The film includes documentary footage shot by Hope Ryden, who filmed the couple and their lawyers as they prepared for trial.

Ms. Buirski says the Lovings were quiet, working-class people who did not like public attention. They did not even attend the legal arguments when their case reached the United States Supreme Court.

NANCY BUIRSKI: "And it wasn’t surprising, given how reticent they were about publicity in general. They were a very modest, humble couple. They really weren’t doing this to change history. They never saw themselves as heroes."

Yet that was what they became, she says, through their desire to remain married and raise their children in a place they loved.

NANCY BUIRSKI: "Apparently they never disagreed about any of it. They were very much in love. And, as far as I'm concerned, they in some ways upend stereotypes, because they weren’t activists. They just wanted to go home and live in Virginia with their families."

On June twelfth, nineteen sixty-seven, the Supreme Court decided that laws against interracial marriage were unconstitutional. The court struck down what were known as anti-miscegenation laws in the sixteen states that still had them.

The couple returned to their Virginia town. Richard built a home where they lived the rest of their lives. He died in nineteen seventy-five when a drunk driver hit his car. Mildred died in two thousand eight.

BARBARA KLEIN: Today, about eight percent of all marriages in the United States are between people of different races. Fifteen percent of new marriages are racially mixed.

Some interracial couples celebrate the anniversary of the Loving decision, June twelfth, as "Loving Day." The day is also increasingly celebrated by supporters of same-sex marriage -- a right that Mildred Loving supported in her later years. Currently same-sex marriage is permitted in five of the fifty states and the District of Columbia.

(MUSIC)

STEVE EMBER: Our program was written and produced by Brianna Blake, with reporting by Mike O'Sullivan and Carolyn Weaver. I’m Steve Ember.

BARBARA KLEIN: And I’m Barbara Klein. You can find transcripts and MP3s of our programs and activities for learning English. Join us again next week for THIS IS AMERICA in VOA Special English.