From VOA Learning English, welcome to The Making of a Nation -- our weekly program of American history for people learning English. I’m Steve Ember.

Last week in our series, we talked about the election of 1828. General Andrew Jackson defeated President John Quincy Adams, after a campaign in which both sides made strong and bitter accusations.

(MUSIC)

Rowdy Supporters Cheer on the New President

On March 4, 1829, Andrew Jackson was sworn in as president. The sky over Washington was cloudy that day. But the clouds parted, and the sun shone through, as Jackson began the ride to the Capitol building.

Thousands of cheering supporters saw this change in weather as a good sign. So many people crowded around the Capitol that Jackson had to climb a wall and enter from the back. He walked through the building and into the open area at the front where the ceremony would be held.

The ceremony itself was simple. Jackson made a speech that few in the crowd were able to hear. Then Chief Justice John Marshall swore in the new president. In the crowd was a newspaperman from Kentucky, Amos Kendall. "It is a proud day for the people," Kendall wrote. "General Jackson is their own president."

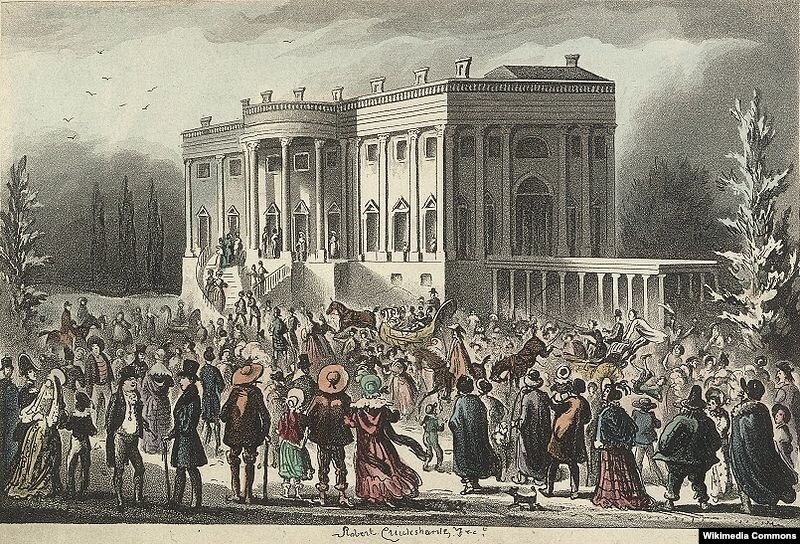

From the Capitol, Jackson rode down Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House. Behind him followed all those who had watched him become the nation's seventh president. The crowds followed him all the way into the White House, where food and drink had been put out for a party.

Everyone tried to get in at once. Clothing was torn. Glasses and dishes were broken. Chairs and tables were damaged. Never had there been a party like this at the president’s mansion.

Jackson stayed for a while. But the crush of people tired him, and he was able to leave. He spent the rest of the day at his hotel room in Virginia.

The guests at the White House finally left after drinks were put on the table outside the building. Many of the people left through windows, because the doorways were so crowded.

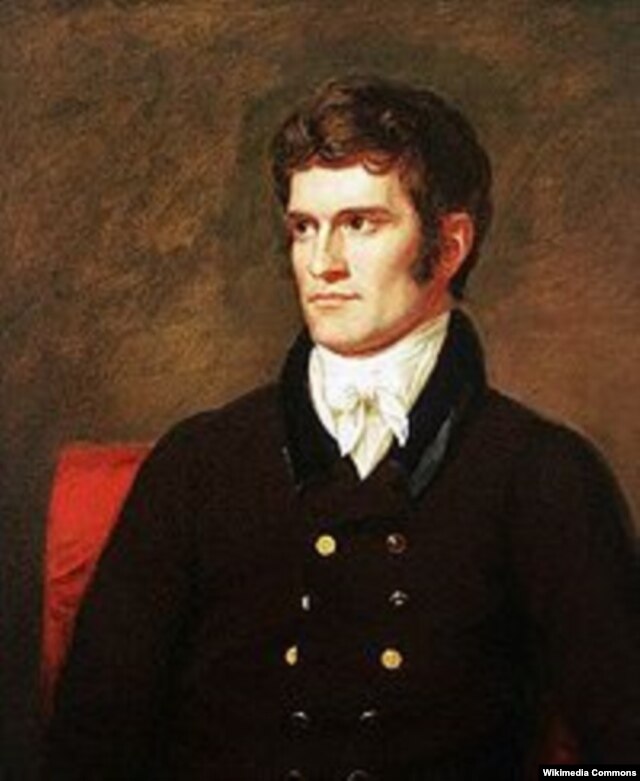

Jackson was popular with many voters, who saw him as representing the common man. But Jackson’s first term seemed to be mostly a political battle with his own vice president, John C. Calhoun of South Carolina.

Calhoun wanted to become the next president. But Jackson preferred his secretary of state, Martin van Buren.

Jackson and Calhoun Split over States' Rights

The split between Jackson and Calhoun deepened over another issue. Jackson learned that Calhoun had once called for Jackson's arrest. Calhoun wanted to punish Jackson for his unauthorized military campaign into Spanish Florida in 1818.

The most important division between the two men was Calhoun's belief about who had more power: the states or the federal government. Calhoun came to believe the rights of the states were stronger than the rights of the federal government. His feelings became well known during a debate on a congressional bill.

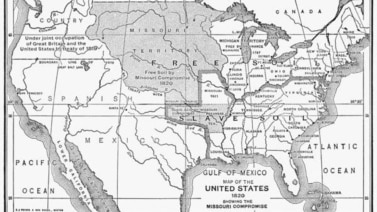

The year before Jackson took office, Congress passed a bill to require taxes on imports. The purpose of the taxes was to protect American industries.

The state of South Carolina, Calhoun’s state, opposed the measure. South Carolina, like other Southern states, had almost no industry. It was an agricultural area. Import taxes would only raise the price of products the South imported.

South Carolina refused to pay the tax. Calhoun wrote a long statement defending South Carolina's action. In the statement, he developed what was called the Doctrine of Nullification. The doctrine declared that the power of the federal government was not supreme.

Calhoun argued that, instead, supreme power belonged to the states. He said states did not surrender this power when they approved the Constitution. In any dispute between the states and the federal government, he said, the states should decide what is right.

Calhoun argued that if the federal government passed a law that any state thought was not constitutional, or against its interests, that state could temporarily suspend the law.

The other states of the union, Calhoun said, would then be asked to decide the question of the law's constitutionality. If two-thirds of the states approved the law, the complaining state would have to accept it, or leave the union. If less than two-thirds of the states approved it, then the law would be rejected. None of the states would have to obey it. It would be nullified — cancelled.

Senators Robert Hayne of South Carolina and Daniel Webster of Massachusetts debated the question of nullification in Congress. Senator Hayne spoke first. He said that there was no greater evil than giving more power to the federal government. The major point of his speech could be put into a few words: liberty first, union afterwards.

Senator Webster said Hayne had spoken foolishly. Liberty and union could not be separated, Webster said. It was liberty and union, now and forever, one and inseparable.

No one really knew how President Andrew Jackson felt about nullification. He made no public statement during the debate. Leaders in South Carolina developed a plan to get the president's support. They decided to hold a big dinner honoring the memory of Thomas Jefferson. Jackson agreed to attend the dinner.

The speeches were carefully planned. They began by praising the democratic ideas of Jefferson. Next they discussed South Carolina's opposition to the import tax.

Finally, the speeches were finished. It was time for toasts. President Jackson made the first one. He stood up, raised his glass, and looked straight at Vice President John C. Calhoun. He waited for the cheering to stop. "Our union," he said, "it must be preserved."

Calhoun rose with the others to drink the toast. He had not expected Jackson's opposition to nullification. His hand shook, and he spilled some of the wine from his glass.

Calhoun was called on to make the next toast. "The union," he said, "next to our liberty, most dear." He waited a moment, then, continued. "May we all remember that it can only be preserved by respecting the rights of the states and by giving equally the benefits and burdens of the union."

President Jackson left a few minutes later. Most of those at dinner left with him.

Jackson Asserts Federal Power over States' Rights

The nation now knew how the president felt. And the people were with him — opposed to nullification. But the idea was not dead among some people in South Carolina.

The nullifiers held a majority of seats in the state's legislature at that time. They called a special convention. Within five days, convention delegates approved a declaration of nullification. They said citizens of South Carolina need not pay the federal import taxes.

The nullifiers also declared that if the federal government tried to use force against South Carolina, then the state would withdraw from the union and form its own independent government.

“This cut very deeply with Jackson. Jackson was a nationalist. He was a great believer in the federal union. He was a flag-waving patriot. As Jackson saw it, nullification was the beginning of the end of the United States as a nation.”

That was historian Daniel Feller. He says Jackson believed in a limited federal government. But that did not mean the people of every state should decide what the constitution means.

“That way lies chaos. As Jackson said, ‘Either we have a national government or we don’t.’ And if Congress does pass laws which might prove to be unconstitutional, we have a procedure for dealing with that. We have the Supreme Court, we have the ability of the people and their elected representatives to appeal to Congress to repeal those laws – to take them back. But you can’t have every state going off on its own and deciding what the Constitution says.’”

Jackson wrote a proclamation answering the nullifiers. In it, he said America's constitution formed a government, not just an association, or group, of sovereign states. South Carolina had no right to cancel a federal law or to withdraw from the union.

Jackson explained that it was his duty, as president, to enforce the laws of the land. Even, as Daniel Feller says, if he had to use force.

“It’s going to come to a test of arms, and this I can quote. And it was in italics, underlined, emphasized in the printed version of the proclamation. ‘Disunion by armed force is treason. Are you really read to incur its guilt?’”

Jackson sent eight warships to the port of Charleston, South Carolina, and soldiers to federal military bases in the state.

While preparing to use force, Jackson offered hope for a peaceful settlement. In a message to Congress, he spoke of reducing the federal import tax that hurt the sale of southern cotton overseas. He said the tax could be reduced, because the national debt would soon be paid.

Congress passed a compromise bill to end the import tax by 1842. South Carolina's congressmen accepted the compromise. And the state's legislature called another convention. This time, the delegates voted to end the nullification act they had approved earlier.

They did not, however, give up their belief in the idea of nullification.

Daniel Feller says one reason is because Southern politicians thought they might need to use nullification later. An anti-slavery movement was beginning to grow in the country. Some southerners worried that Congress would one day make laws they did not like against slavery.

The issues of slavery and states’ rights would continue to be areas of conflict. Eventually, they would help start the Civil War in 1861.

But well before that, President Andrew Jackson would fight a different battle. The struggle over the Bank of the United States will be our story next week.

I’m Steve Ember, inviting you to join us next time for The Making of a Nation — American history from VOA Learning English.