STEVE EMBER: Welcome to THE MAKING OF A NATION – American history in VOA Special English. I’m Steve Ember.

(MUSIC)

This week in our series, we continue the story of America's thirty-third president, Harry Truman.

Truman was sometimes called an "accidental" president. He only became president because he was vice president when Franklin Roosevelt died in nineteen forty-five.

In the election of nineteen forty-eight, Truman ran for a full term. As we told you last week, many experts predicted he would lose. But voters chose him over the Republican Party candidate, Thomas E. Dewey, the governor of New York. Americans also elected a Congress with a majority from Truman's Democratic Party.

The president might have expected a Congress led by his own party to support his policies. But that did not always happen. Time after time, Democrats from southern states joined in voting with conservative Republicans. Together, these lawmakers defeated some of Truman's most important proposals. One of the defeated bills was a proposal for health care insurance for every American.

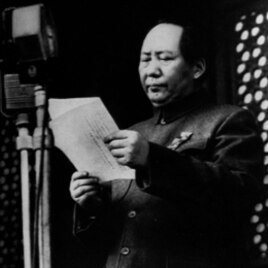

One of the major issues during Truman's second term was fear of communism. After World War Two, Americans watched as one eastern European nation after another became an ally of the Soviet Union. Soviet leader Josef Stalin wanted to see communism spread around the world. And Americans watched as China became communist in nineteen forty-nine, as forces led by Mao Zedong defeated the Chinese Nationalists after a civil war that had lasted more than ten years.

During this tense period, there were charges that communists held important jobs in the United States government. These fears, real or imagined, became known as the "Red Scare."

SENATOR JOSEPH McCARTHY: “Even if there were only one communist in the State Department –- (repeats) Even if there were only one Communist in the State Department, that would still be one communist too many.”

A Republican senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy, led the search for communists in America. In speeches and congressional hearings, he accused hundreds of people of being communists or communist supporters. His targets included the State Department, the Army and the entertainment industry.

Senator McCarthy often had little evidence to support his accusations. Many of his charges would not have been accepted in a court of law. But the rules governing congressional hearings were different. So he was able to make his accusations freely.

Many people lost their jobs after they were denounced as communists. Some had to use false names to get work. A few went to jail briefly for refusing to cooperate with McCarthy.

The senator continued his anti-communist investigations for several years. By the early nineteen fifties, however, more people began to question his methods. Critics said he violated democratic traditions.

In nineteen fifty-four, the Senate finally voted to condemn his actions. McCarthy died three years later.

(MUSIC)

There were problems caused by the fear of communists at home. But President Truman also had to deal with the threat of communism in other countries.

He agreed to send American aid to Greece and Turkey. He also supported continuing the Marshall Plan. That was the huge economic aid program that helped rebuild western Europe after World War Two. Many historians say the Marshall Plan prevented western Europe from becoming communist.

The defense of western Europe against Soviet communism led Truman to support the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. NATO began in nineteen forty-nine with the United States, Britain, Canada, France and eight other nations.

The treaty that created NATO stated that a military attack on any member would be considered an attack on all of them.

Truman named General Dwight Eisenhower to command the new organization. General Eisenhower had been supreme commander of Allied forces in Europe in World War Two.

In his swearing-in speech in nineteen forty-nine, Truman urged the United States to lend money to other countries to aid their development. He also wanted to share American science and technology.

In nineteen fifty-one, the president asked Congress to establish a new foreign aid program. The aid would go to countries threatened by communist forces in Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, East Asia, South Asia and Latin America. Truman believed the United States would be stronger if its allies were stronger.

President Truman believed that many of the world's problems could be settled by other means besides military force. But he supported and used military power throughout his presidency.

On June twenty-fifth, nineteen fifty, forces from North Korea invaded South Korea. Two days later, the United Nations Security Council approved a resolution urging UN members to help South Korea resist the invasion. At first President Truman agreed to send American planes and ships. Later he agreed to send American ground forces.

The president knew his decision could start World War Three if the Soviet Union entered the war on the side of communist North Korea. Yet he felt the United States had to act. Later, he said it was the most difficult decision he made as president.

Truman named Army General Douglas MacArthur to command all United Nations forces in South Korea.

Most of the fighting in the Korean War took place along the geographic line known as the thirty-eighth parallel. This line formed the border between North and South Korea.

Many victories on the battlefield were only temporary. One side would capture a hill; then the other side would recapture it.

In September of nineteen fifty, Mac Arthur led the UN land and sea attack at Inchon, pushing the North Koreans back across the border. There was hope that the war could end by Christmas, December twenty-fifth.

In late November, however, troops from China joined the North Koreans. Thousands of Chinese soldiers helped push the UN troops south. General MacArthur wanted to attack Chinese bases in Manchuria. President Truman said no. He did not want the fighting to spread beyond the Korean peninsula. Again, he feared that such a decision could start another world war.

MacArthur strongly believed he could end the war quickly by extending it to the Chinese mainland. He publicly denounced Truman’s policy, saying “There is no substitute for victory.”

Truman felt that the general left him no choice. In April of nineteen fifty-one, he dismissed MacArthur.

HARRY TRUMAN: ”It was with the deepest personal regret that I found myself compelled to take this action. General MacArthur is one of our greatest military commanders. But the cause of world peace is much more important than any individual.”

In the United States, military leaders are expected to obey their commander in chief -- the president. While some Americans approved of the general's dismissal, many others supported MacArthur. Millions greeted him when he returned to the United States. There were huge parades in his honor in San Francisco and New York.

In fact, few leaders in the twentieth century could boast the support MacArthur had. Almost seven million people attended the ticker tape parade given to him by New York City. And that almost doubled the size of the one given to another returning World War Two hero, General Dwight Eisenhower.

MacArthur gave his farewell speech to a joint session of Congress on April nineteenth, nineteen fifty-one.

DOUGLAS MacARTHUR: “I am closing my fifty-two years of military service. When I joined the Army, even before the turn of the century, it was the fulfillment of all of my boyish hopes and dreams. The world has turned over many times since I took the oath on the plain at West Point, and the hopes and dreams have long since vanished, but I still remember the refrain of one of the most popular barrack ballads of that day which proclaimed most proudly that old soldiers never die; they just fade away.

And like the old soldier of that ballad, I now close my military career and just fade away, an old soldier who tried to do his duty as God gave him the light to see that duty. Goodbye." [Applause]

(MUSIC)

On the Korean peninsula, the war continued. Ceasefire talks began in July of nineteen fifty-one. But the conflict would last for another two years until a truce was declared. The Korean War armistice agreement was signed on July twenty-seventh, nineteen fifty-three.

(MUSIC)

Nineteen fifty-two was a presidential election year in the United States. Harry Truman was losing popularity because of the continuing war in Korea and economic problems at home. At the same time, Dwight Eisenhower, a military hero from World War Two, was thinking of running for president as the Republican candidate.

Harry Truman had made many difficult decisions as president. In March of nineteen fifty-two, he made one more. He announced that he would not be a candidate for re-election.

The nineteen fifty-two presidential election will be our story next week.

You can find our series online with transcripts, MP3s, podcasts, and pictures at voaspecialenglish.com. And you can follow us on Facebook and Twitter at VOA Learning English. I’m Steve Ember, inviting you to join us again next week for THE MAKING OF A NATION -- American history in VOA Special English.

Contributing: David Jarmul

This was program #203. For earlier programs, type "Making of a Nation" in quotation marks in the search box at the top of the page.