From VOA Learning English, welcome to The Making of a Nation, our weekly program of American history for people learning American English. I’m Steve Ember.

Eighteen fifty-two was a presidential election year in the United States. The Democratic Party held its nominating convention in Baltimore, Maryland. The meeting opened in June of 1852. Delegates agreed that a man must win two-thirds of the convention's votes to be the Democratic candidate.

On the first ballot, no one received two-thirds of the vote. So the voting continued. Finally, on the 47th ballot, support began to increase for someone considered an unlikely candidate. His name was Franklin Pierce.

Pierce was from the northeastern state of New Hampshire. He was a lawyer and former state lawmaker. He also had served in the United States Senate and House of Representatives. He became an officer in the Army during the U.S. war with Mexico.

On the 49th ballot, Pierce won the Democratic nomination. He would be the party's candidate for president.

“Pierce was a passionately loyal adherent of the Democratic Party and of its principles of negative governance domestically and spread eagle expansionism in foreign affairs.”

Historian Michael Holt wrote a book about Franklin Pierce. Mr. Holt describes Pierce as someone who was like most Democrats at the time. In other words, he did not think the federal government should intervene much in efforts to help build up and develop the nation. But he wanted the United States to play a big and powerful role internationally. Naturally, Democrats did not agree on every policy issue. In 1852, the party was sharply divided on whether the government should — or could — permit slavery to continue in the United States. But Democrats decided to limit their fighting with each other during the election campaign. And they all agreed to support Pierce.

The Whig Party held its presidential nominating convention in Baltimore two weeks after the Democrats met. The same thing that happened at the Democratic convention now happened at the Whig convention. Delegates voted over and over again. But no man got enough votes to win. It took 53 ballots before one of the men -- General Winfield Scott -- won the nomination.

On Election Day, Pierce won a crushing victory. The Democrats won not only the presidency, but also strong majorities in Congress. The Democrats’ victory was so great that many people thought the Whig party was finished.

In fact, many Whigs themselves hoped their party was destroyed. Like the Democrats, Whigs disagreed with each other about slavery. Northern Whigs wanted to form a new anti-slavery party. And southern Whigs wanted to form a party that would better represent their interests.

The Whigs lost badly in the 1852 elections because, unlike the Democrats, they were not able to bridge the differences between their northern and southern members.

Franklin Pierce was 48 years old when he took office. He was the youngest man yet to be elected president. He was charming and made friends easily.

But those who knew Pierce best worried about him. They knew that under all his friendly charm, he was a weak man. They feared the duties and problems of the presidency would be too great for him to deal with.

Pierce also faced a difficult situation in his personal life. Two of his children had died when they were babies. A third child was killed in a train accident shortly before Pierce moved to the White House.

In addition, his wife Jane did not like living in Washington, D.C. She did not support her husband's campaign for presidency. Years earlier, she had urged him to resign from the Senate and return to New Hampshire. She did not want to go back to Washington.

When her husband was elected, she agreed to live there. But she rarely saw anyone. One of her close friends took her place at public events.

Historian Michael Holt says Franklin Pierce’s main goal as president was to keep his party united. One way to maintain party unity was to adopt popular Democratic policies. He promised strong support for expanding the territory of the United States. He also promised a strong foreign policy.

During his term in office, Pierce successfully negotiated with Britain to gain American fishing rights along the coast of Canada. He also supported diplomatic and trade talks with Japan. However, he was unsuccessful in an attempt to buy Cuba from Spain.

National issues presented President Pierce with a more difficult problem. Now that the election was over, some Democrats felt it was time once again to raise the issue of slavery.

The Compromise of 1850 had settled the question of slavery only in the western territories. But anti-slavery activists said the compromise should have done more to end slavery throughout the country. And pro-slavery activists said the agreement did not protect slave owners’ rights. They did not want the federal government to intervene in slavery anywhere.

As president in 1853, Pierce had to choose between the competing sides. He could support the Compromise of 1850 and say the dispute over slavery was settled.

Or Pierce could try to make peace with both anti- and pro-slavery extremists. Giving the extremists jobs in his administration would be the easy way to satisfy their demands. And that was the policy Pierce chose.

“Contemporaries at the time predicted that this attempt to share the plums would wreck the party, and it did.”

Historian Michael Holt says Pierce sought to include men from competing sides of the Democratic Party in his cabinet.

Pierce named William Marcy of New York as Secretary of State. Marcy wanted to limit the spread of slavery and keep the Union together.

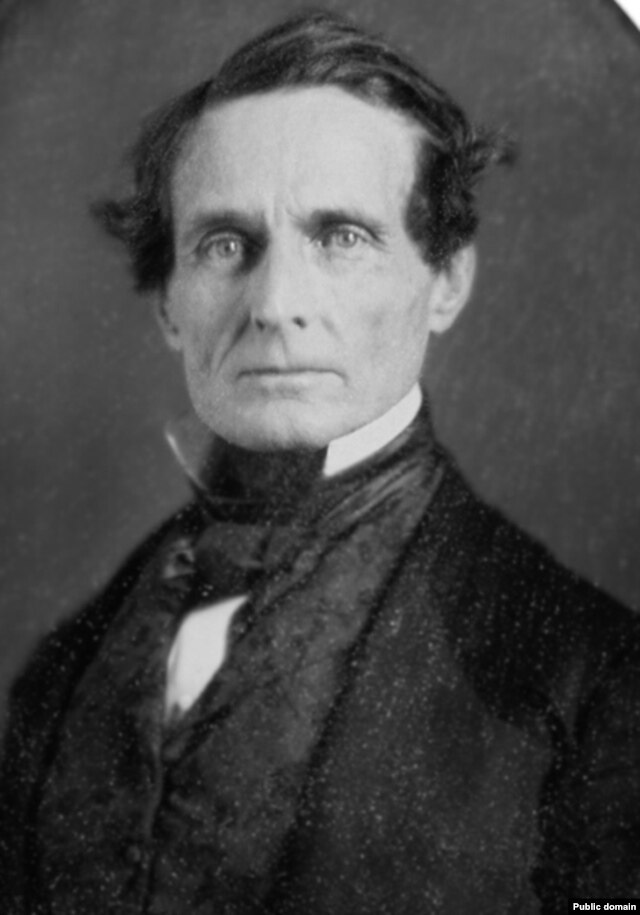

Jefferson Davis of Mississippi was named Secretary of War. Davis -- more than any other man -- represented southern slave owners. He threatened to take the South out of the Union if the government set any limits on slavery.

Caleb Cushing of Massachusetts was named Attorney General. Although a northerner, Cushing was a friend of many southerners. He was a very able man, but his loyalties were not clear. James Buchanan of Pennsylvania was named Minister to Britain.

All these men had strong ideas about the future of the United States. President Pierce found it difficult to control them. One senator even said the administration should not have been called the Pierce administration, because Pierce did not lead it. He said it was an administration of enemies of the Union who used the president's name and power for their own purposes.

As president, Franklin Pierce faced another difficult question. Where should the United States build its new railroads?

The country had expanded and white settlers were moving west. Many were hungry for good transportation. They wanted railroads that reached across the continent, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. Engineers decided that four new rail lines would be possible. They could cross the southern, central, or northern parts of the United States.

Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas, a Democrat, proposed that three of the lines be built. He said the government could give land to the railroad companies. The companies could then sell the land to get the money they needed to build the lines.

A Senate committee discussed the issue. Its members proposed that only one railroad line be built. But which one?

Many congressmen believed a southern line would be best. There would be little snow in winter. And the railroad would cross lands that were already organized as states or official territories.

A northern or central line would face severe winter weather. And it would have to cross a large, wild area called Nebraska. Nebraska was neither a state nor a territory. As a result, it did not yet have a local government that could support a railroad. In addition, many congressmen did not want Nebraska to develop a government. The reason, once again, was slavery.

Michael Holt says members of President Pierce’s party hoped the effort to organize Nebraska would unite Democrats once again. Instead, Mr. Holt says, Nebraska territory caused more conflicts and ruined Pierce’s administration. The bill increased divisions between Democrats and Whigs, pro-slavery activists and anti-slavery abolitionists. And, it brought the country one step closer to civil war.

As one northerner wrote, "It was said hundreds of years ago that a house divided against itself cannot stand. The truth of this saying is written on every page in history. It is likely that the history of our own country may offer fresh examples to teach this truth to future ages."

The bitter dispute over Nebraska will be our story next week. I’m Steve Ember, inviting you to join us next time for The Making of a Nation — American history from VOA Learning English.