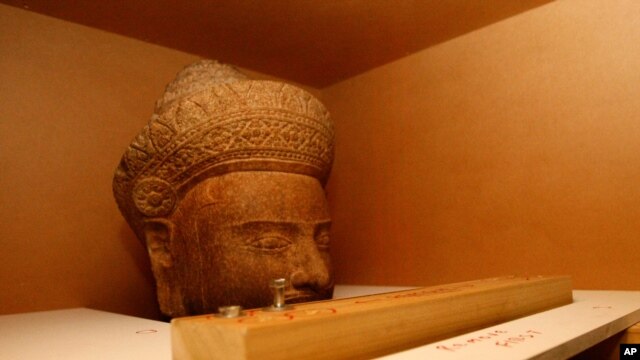

Over the past 40 years, Cambodia’s cultural treasures have been under attack. Many artifacts have disappeared from ancient religious centers and other historic sites across Cambodia. A large number of the objects were secretly removed from the country and sent to art museums and private collections around the world.

New research shows that much of this activity was the work of organized crime. It also suggests that most pieces have disappeared from public view, probably forever.

Cambodia’s 1,000-year-old temples and other historic areas first came under attack in 1970, at the start of the Cambodian civil war. The looting and raids continued until the fighting stopped about 30 years later. One incident in the early 1970s involved government soldiers. They used a military helicopter to airlift ancient artifacts from a 12th Century fort in the northwest.

At the same ruins in 1998, generals tore down and removed 30 tons of the structure. Six military trucks loaded with artifacts were sent toward the border with Thailand. Only one of the six trucks was stopped and its objects returned. The rest disappeared.

For years, researchers believed that such well-organized attacks were rare, and that most of the raids involved local people. But a new study shows just the opposite. The University of Glasgow in Scotland organized the study.

Tess Davis is a lawyer and an archeologist – someone who studies past human life and activities. She was a member of the study team.

“The organized looting and trafficking of Cambodian antiquities was tied very loosely to the Cambodian civil war and to organized crime in the country. It began with the war but it long outlived it, and was actually a very complicated operation, a very organized operation, that brought antiquities directly from looted sites here in the country to the very top collectors, museums and auction houses in the world.”

Tess Davis says the Cambodian and Thai militaries were often in involved in the attacks, as was organized crime. And she says local people were often forced to work as laborers.

Researchers say a dealer in Bangkok provided the link between the criminals and the collectors and museums.

The University of Glasgow study is part of an international effort designed to improve understanding of how the market for stolen artifacts operates. It is the first to show how works of art travel the full distance from ancient sites to the hands of art collectors.

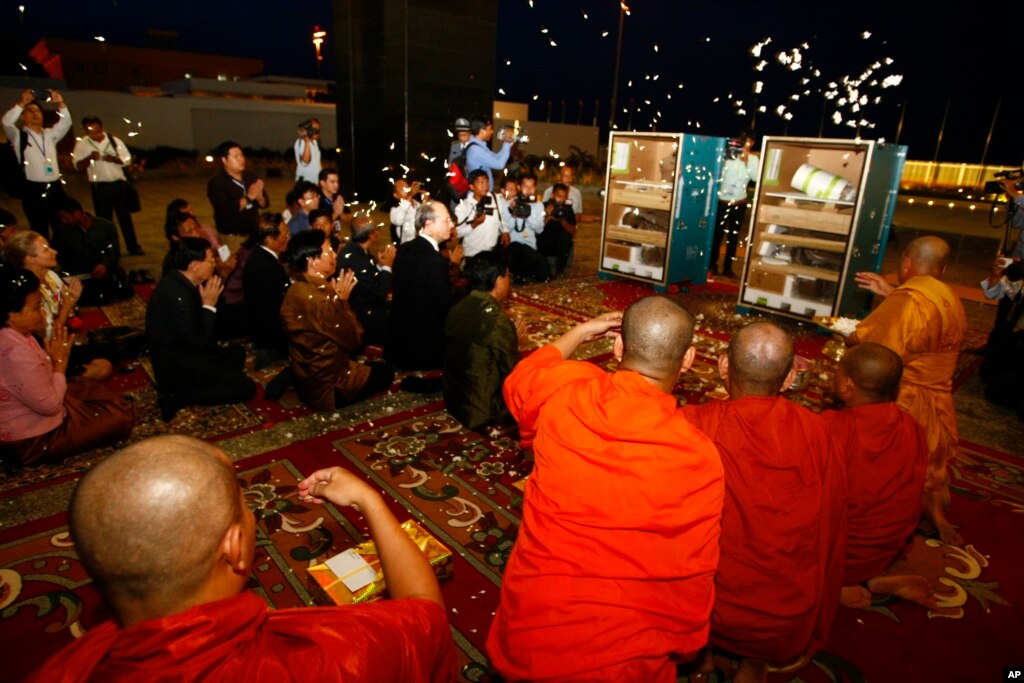

The destruction of Cambodia’s cultural treasures is sad, but there are some victories. Last month, Cambodia welcomed back three 1,000-year-old statues. The three were taken in the 1970s from a temple area. Last year, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art returned two other statues in that group.

All five objects were taken to the National Museum of Cambodia in Phnom Penh. Specialists are preparing them for public display later this year.

The head of the National Museum of Cambodia says Cambodian officials are taking steps to protect culturally important artifacts. That includes documenting all objects kept in museums and those at unprotected areas.

Many of these artifacts are worth a lot of money. They are often targets in war. This is what has happened in recent years in places such as Iraq, Egypt, and Syria.

The money earned from artifact sales often is used to buy arms. Tess Davis says that fact alone should wake up the world to the biggest picture: that the looting and sale of antiquities is often the work of organized crime and armed groups.

“And that link should be a red flag for the world today because we are seeing the same thing repeated today in Egypt and Syria and Iraq, and with very serious consequences – not just for those countries but also again for the world economy and for global security. The money that collectors in New York are spending on antiquities from around the world is going into the pockets of some very bad people. And I think the art world needs to step up and recognize their role in what’s happening in these countries.”

In Cambodia, the worst of the looting has now stopped – in part, because there is little left to take. But the coming years will see more cultural treasures discovered, and experts say it is likely that they also will be in danger.