From January to September of this year an estimated 230 migrants died trying to cross the border from Mexico into the United States. This is according to a new report released by the International Organization for Migration. The organization says that number might be higher.

The exact number of victims is not known. Their names are also not known.

But a university professor in Texas is trying to give closure to families who have lost relatives on the border.

Holding a human rib bone in her gloved hand, Baylor University Anthropology Professor Lori Baker notes signs of postmortem damage -- damage done after death.

“This would be indicative of vulture damage.”

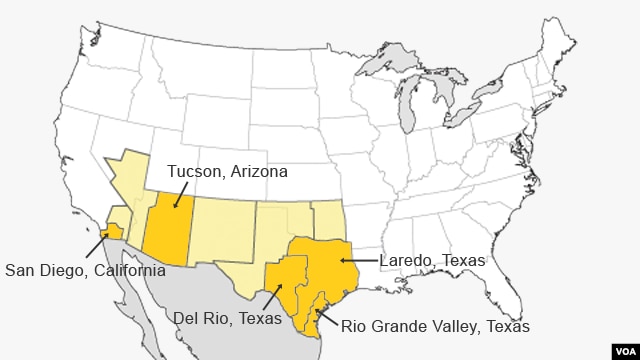

The bone is part of a skeleton, a set of bones. It was found in the lower Rio Grande River valley of Texas, close to the Mexican border. People dying in the desert, their remains being eaten by scavenger birds such as vultures, are realities of Ms. Baker’s work.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security estimates that more than 6,000 immigrants have died crossing into the United States from Mexico in the past 15 years.

Local officials have found hundreds of unidentified bodies in south Texas alone. They have buried them in mass graves in local cemeteries.

Families have no bodies to bury, no graves to visit. To help them get closure, Professor Baker and her students have been digging up bodies to try to identify them.

Lori Baker says that in most cases, the people died of the heat.

“There are a few traumatic things we need to look at, but, all in all, most of the individuals that we see die of heat exhaustion.”

She says that smugglers often leave immigrants in unpopulated areas where there is no water or shelter. Ms. Baker says that it is hard to know how many have died.

“So there are probably a lot more individuals who have died and just have not been found.”

Families in Mexico and Central America have spent many years looking for lost loved ones. Often, officials say, immigrants carry no identification. If they die, they are gone without leaving a trace.

Student volunteers help the cause

Ms. Baker understands the problems local officials face in rural U.S. counties. They have little money. A coalition of Texas sheriffs-- law officers --says each dead migrant they find costs a county $5,000 to remove, examine and bury.

A team of student volunteers helps Professor Baker. The volunteers take part in the hard, sad work of digging up bodies for the forensics. But they say they also share Prof. Baker’s sense of mission.

The work can be not only physically hard. It can be emotionally hard as well.

Jennifer Husak is a recent Baylor graduate. She spent two summers working with Lori Baker in south Texas. She remembers that the most difficult time in this work came early on, when she examined the bones of a baby. Ms. Husak says it was hard for her to think about the work. At that moment, the bones had a family story connected to them.

“It was very difficult for me at first to think about a mother not being able to watch her child grow up. It was very difficult.”

Chelsea Art is studying anthropology at Baylor University. She worked with Lori Baker at a cemetery about 100 kilometers north of the border. Hundreds of bodies have been found there over the years. Not many people live in the area. Immigrants are often extremely tired and in great need of water by the time they arrive.

Ms. Art says working in the heat gave her some idea, however small, of how terrible it must be for an immigrant to be out in the open without any support.

Personal mission

It has also become personal for Lori Baker. She says she hopes to give human respect, or dignity, to those who have died trying to cross the border.

“I hope that through the work we do we will be able to restore some human dignity to that person by giving them a name.”

Ms. Baker and her volunteers have worked with more than 170 bodies and have identified three. She has spoken to family members of these people and knows firsthand how much it means to them.

The final goal for Lori Baker is to return identified remains to their families. Then at least they can have a burial place where they can say prayers and leave flowers.

I’m Anna Matteo.

VOA’s Greg Flakus reported this story from Texas. Anna Matteo wrote it for Learning English.

Words in this Story

scavenger - n. an organism (as a vulture or hyena) that usually feeds on dead or decaying matter

cemetery - n. a place where dead people are buried

closure - n. a feeling that a bad experience (such as a divorce or the death of a family member) has ended and that you can start to live again in a calm and normal way

smuggle - v. to move (someone or something) from one country into another illegally and secretly. A smuggler is someone who smuggles.

forensic - adj. relating to the use of scientific knowledge or methods in solving crimes

dignity - n. the quality of being worthy of honor or respect

mission - n. a task that you consider to be a very important duty

trace - n. a sign or evidence of some past thing

Now it’s your turn to use these Words in this Story. In the comments section, write a sentence using one of these words and we will provide feedback on your use of vocabulary and grammar.