Lebanon is a country where religious differences and a permissive culture can lead to conflict. The Lebanese government has long been active in guiding the country’s arts and culture. Now, some activists and writers are taking the fight for free speech to the courts. They accuse the government of acting without concern for what is right or fair.

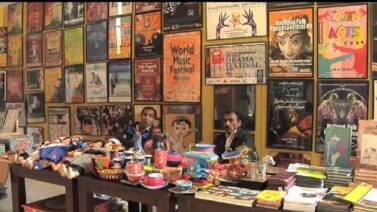

A civil rights group called MARCH helps Lebanese playwrights. MARCH says it provides support to writers whose works failed to survive the government’s required approval process.

The group sought approval of four plays that explore issues often barred from public discussion in Lebanon. Those issues are politics, the country’s civil war, religion and homosexuality.

Lea Baroudi of MARCH says Lebanese officials never gave approval to the four plays. Her group is now launching a court appeal. It wants any decision to restrict information based on rules, not some official’s personal opinion.

Ms. Baroudi told VOA that, “A lot of people think there is no censorship in Lebanon, or that the laws are pretty correct. What we wanted to show and prove is that the laws on censorship are completely arbitrary. All they do is oppress arts and culture in Lebanon -- as the only people who suffer are the artists and play directors.”

The deadly attack on the French magazine Charlie Hebdo fueled debate about the limits of free speech. More than 100 people gathered in the center in Beirut in a show of support for free speech. However, others defend the actions of the Lebanese government. They say free speech can go too far, given the country’s many religious groups. They note that it can be especially dangerous at a time of unrest in nearby countries.

Lea Baroudi says the very idea of censorship can be a misplaced one. She says the policy of limiting discussion on many issues, as a way to please every group, is not making things better. In her words, “It’s making them worse, and it’s building up the tensions.”

Lebanon’s general security department has the job of restricting information. In the past, the agency has said it was simply following the current laws on censorship.

But MARCH says these laws are both unclear and out of date. The group says the general security office now states it did not ask for a ban, but instead requested that parts of the plays be changed. MARCH says that decisions over censorship are often announced, but rarely given in writing. It says this makes the orders more difficult to fight. It also said the ban remains in place, and that such disorder demonstrates the need to reform the process.

Lebanon has at least four legal justifications for banning or restricting material. They include if it “is offensive to the sensitivities of the public,” “exposes the state to danger” and “is propaganda against state interests.” Another justification is being “disrespectful to public order, morals and good ethics.”

The result is that a number of foreign works have been banned. They include American John Steinbeck’s famous work Of Mice and Men and writer Dan Brown’s book The Da Vinci Code. Songs from Lady Gaga, Frank Sinatra and other artists have also been banned in Lebanon.

Firas Talhouk studies government restrictions for the Lebanese group SKeyes Media. He says the laws are often decided according to the politics of the day. “It depends on the political and security situation in Lebanon and the region. It also depends on the political players and the personalities of those in charge,” he says.

In addition, the pressure of censorship extends beyond the government. “There are some politicians you cannot talk about, but it’s not only because of censorship,” he says. “It is also because of social pressures and self-censorship by individuals.”

Writer and director Lucien Bourjelly confirms that artists now self-censor their work to make sure it gets approval from the government. Mr. Bourjelly wrote a theatrical study of the censorship process. Lebanese officials banned it.

Lebanon’s artistic community is facing many tests. Yet the community promises it will continue to create and to push the limits on what the government considers taboo.

In the words of Lucien Bourjelly, “Art is where we make a stand. If we don’t make it there, freedom of expression is lost for everyone – for artists, for journalists and for everyday people.”

I’m Jim Tedder.

This report was based on a story from reporter John Owens in Beirut. George Grow wrote this story for VOA Learning English. Mario Ritter was the editor.

Words in This Story

permissive - adj. giving people freedom to do what they want to do

process - n. an operation or series of changes leading to a desired result

homosexuality - n. the quality of having a sexual desire for someone of the same sex as oneself

censorship - n. the system of banning or restricting use of information

taboo – n. something considered unacceptable