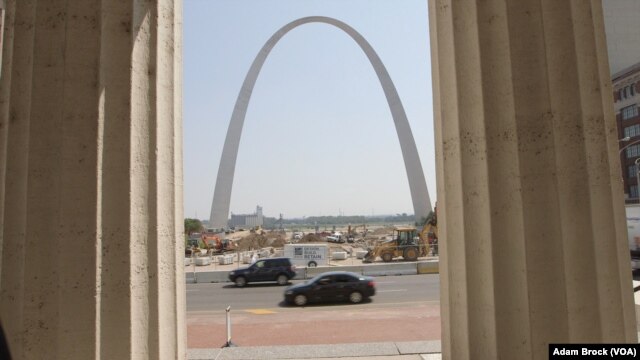

America’s tallest monument dominates the skyline of St. Louis, Missouri, the largest city onbetween Chicago and Los Angeles.

The Gateway Arch represents the beginning of the American West. It also commemorates St. Louis’s role in the nation’s westward expansion.

Early settlers in the 1800s depended on the city as a final chance to stock up on food and other provisions before making the long journey west.

The Gateway Arch towers above St. Louis on the banks of the Mississippi River. The 192-meter-tall stainless steel arch is the tallest structure of its kind in the world.

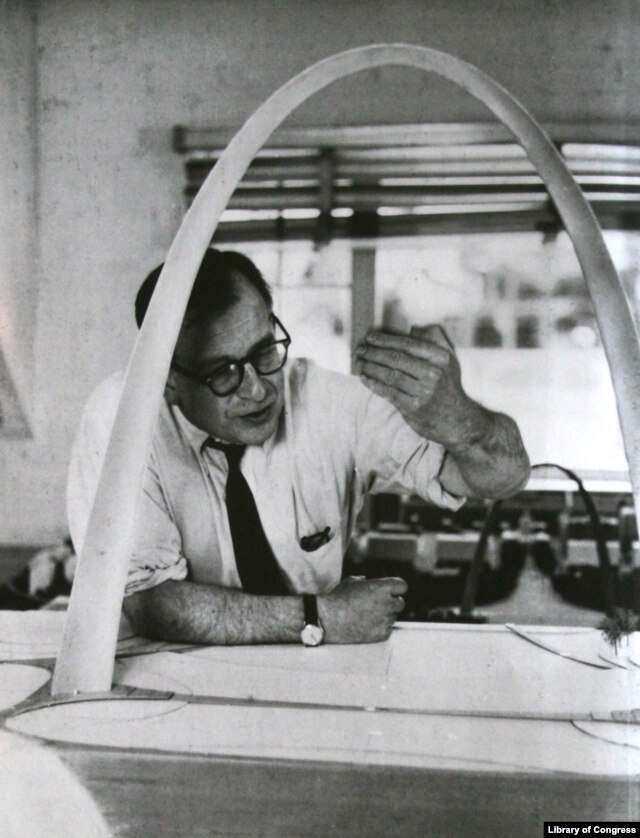

Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen won a national competition for a design of the proposed monument in 1947.

Construction of the Gateway Arch was completed in 1965.

Karen Stoeber works at the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, which includes the Gateway Arch.

“The arch commemorates the 300,000 people who, after Jefferson made the Louisiana Purchase, moved from the eastern part of the country west...and this was kind of the meeting place for all of them. This was the last big city, where they could provision up before they went west.”

The Gateway Arch has an internal tram system. Visitors can ride to the top of the arch for a good view of St. Louis and the Mississippi.

"And Eero Saarinen, the architect, made it in the shape of a gate...kind of like you open the gate and step into the new country.”

That “new country” held promise. But it held tragedy too.

The “Westward Expansion” of the 1800s brought many Americans to settle on the Great Plains of the United States. Missouri, Oklahoma and Texas offered good land for farming and raising cows in the early years of settlement.

The Dust Bowl

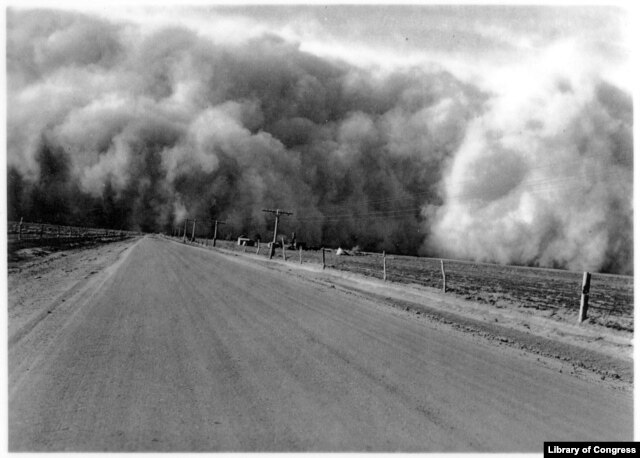

Then, in the 1930s, disaster struck. A severe and long-lasting drought destroyed crops across the southern Great Plains. Over-farming, or planting too many crops, had destroyed the area’s natural grasslands. This left the land unprotected from the wind storms that arrived with the drought.

The result was several years of massive, deadly dust storms. The huge area of prairie land in the U.S. became known as the “Dust Bowl.” The period of time came to be called the “Dirty Thirties.”

Farms, equipment and homes were sometimes buried in the huge dust storms.

At the same time, the U.S. was experiencing a major economic crisis known as the Great Depression.

Mother Nature and the failed economy displaced millions of people who lived in the Dust Bowl. And so began the largest human migration in the United States. Route 66 played a major part in that westward movement of desperately poor people.

Hundreds of thousands of people headed west. Many were poor farmers. But teachers, doctors and other professionals also fled the Dust Bowl. Entire towns disappeared. Whole communities “hit the trail.”

For many, that trail was the newly commissioned Route 66. The highway crossed much of the Dust Bowl into the more fertile land of California.

The migrants collected their families and the possessions they could keep. They loaded them into wagons and cars. The trek west continued through the 1930s until the beginning of World War II.

“Dust Storm Disaster” by American folk legend Woody Guthrie paints a picture of the Route 66 travelers.

It covered up our fences, it covered up our barns, It covered up our tractors in this wild and dusty storm. We loaded our jalopies and piled our families in, We rattled down that highway to never come back again.

Migrant camps sprung up along Route 66. Most were along narrow manmade waterways used to water crops. This provided the migrants with water for drinking, cooking and bathing. These poor, temporary villages were called “ditch bank camps.”

The Mother Road

The writer John Steinbeck traveled Route 66 and visited some of these camps in 1936 and 1937. He reported about them for a newspaper. Steinbeck’s news stories were central to the creation of his most famous novel, “The Grapes of Wrath.” The novel made the road famous and gave it its most popular nickname, the “Mother Road.”

That book tells the story of the Joads, a poor migrant family that travels Route 66 from Oklahoma to California during the Dust Bowl period.

Steinbeck writes:

“66 is the path of a people in flight, refugees from dust and shrinking land, from the thunder of tractors and shrinking ownership, from the desert’s slow northward invasion, from the twisting winds that howl up out of Texas, from the floods that bring no richness to the land and steal what little richness is there. From all of these the people are in flight, and they come into 66 from the tributary side roads, from the wagon tracks and the rutted country roads. 66 is the mother road, the road of flight.”

Today, it is mostly tourists who travel the full distance of Steinbeck’s “mother road.” The Dust Bowl and the Depression have long passed.

Route 66 is no longer a “road of flight.” But it remains a powerful symbol of America’s westward migration that continues to this day.

I'm Ashley Thompson.

And I'm Caty Weaver. Join us next week as we continue our journey down the Mother Road.

Words in This Story

provision – n. a supply of food and other things that are needed

tower – v. to be much taller than (someone or something)

commemorate – v. to exist or be done in order to remind people of (an important event or person from the past)

migration – n. the movement of people from one country or place to live or work in another

trek – n. a long and difficult journey

jalopies – n. (informal) an old car that is in poor condition

rattle – v. to make quick, short, loud sounds while moving

tributary – n. a stream that flows into a larger stream or river or into a lake