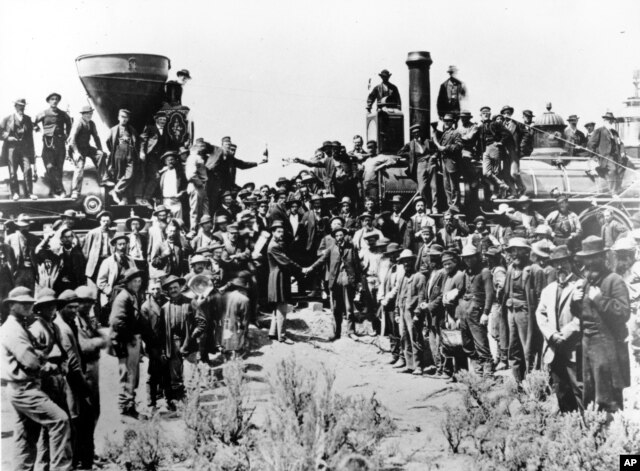

Next year marks the 150th anniversary of when large numbers of Chinese started working on a huge project in the United States. They helped to build America’s first transcontinental railroad, connecting the East Coast with the West.

Very little is known about the Chinese railroad workers and what happened to them after the project was finished. Stanford University in California wants to learn more about the lives of these men by reaching out to their families. Pat Bodner has more.

Two words -- hopelessness and bravery -- could very well describe what led the ancestors of Bill Yee to come to the United States.

“I don’t think I could do it. To come to a strange country and don’t know a word of English. But I guess it’s between eating or starving. I guess you have to do what you have to do for your family.”

His ancestors came from southern China. They became part of an important event in American history.

“My great-great-grandfather came over during the ‘gold rush’ days and he returned back to China as a wealthy man. And then my great-grandfather came over to work on the railroad. He came over as a -- to work with black gunpowder, black powder on the railroad and he died working on the railroad.”

But that did not stop his grandfather from coming to the U.S. on false papers. He operated a laundry, a service for cleaning clothing. Bill Yee’s father continued to head the business.

“Things were pretty bad in some parts of China at that time. So they came to America at all costs.”

Shelley Fisher Fishkin wants to hear stories like this.

“The records of specific individuals and their names and experiences are so sparse.”

Ms. Fishkin is helping to direct the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project at Stanford University. She is working with experts in Asia to look for descendants of railroad workers on both continents to learn more about the lives of these men.

“Many of the Chinese workers who came to work on the Transcontinental and other railroads returned to China after their work was done, created families there. Some of them had families who they left when they came here and they may have descendants in China.”

The goal is to create a digital record of old objects, documents and spoken histories from the families of the railroad workers. Historians would then piece together the mystery of who they were and what happened to them.

“…and the U.S. could not have become the modern industrial nation it did without the railroads, and the railroads would not have come together when they did without the crucial work of these Chinese workers.”

Jonathan Wong’s ancestor studied English and left China to work as a language assistant on the Transcontinental Railroad. He later brought his family to the United States, and they settled in San Francisco.

“He kind of had a different experience than having to do labor. He wouldn’t go home feeling that he was going to be in danger the next day. It was more of a closer relationship obviously with the white community, his white superiors. But obviously, I know that he was still treated as if he was the inferior minority.

Shelley Fisher Fishkin says it was part of life as a Chinese railroad worker.

“They suffered greatly from discrimination and from prejudice. They were paid less than their Euro-American workers.”

Bill Yee wants his six children and 19 grandchildren to know their family history.

“They have to appreciate the sacrifice that our grandparents did for us. Otherwise I might be working in the rice fields now. So it really brings a big opportunity to this generation.”

Through the Stanford University project, the lives of these men can be remembered. This will help others more fully understand their part in American history.

I’m Pat Bodnar.