For VOA Learning English, this is Everyday Grammar.

Today we have good news for English learners.

Just as words come and go in English, so do grammar rules. Today we will show you three difficult grammar rules that are disappearing from American English.

Don’t end a sentence with a preposition

When I was in school, my English teacher told me that it is wrong to end a sentence with a preposition. For example, “Who are you talking to?”

The last word of the sentence, to, is a preposition. In traditional grammar, you would have to move the preposition before the subject.

“To whom are you talking?”

The rule applies to statements as well as questions.

“I know where you’re from,” would be, “I know from where you come.” Today, it sounds very old-fashioned to speak this way.

The rule against ending a sentence with a preposition goes back to the 18th century, when it was fashionable to borrow grammar rules from Latin.

British grammarians celebrated Latin as a pure and logical language. They thought they could improve English by importing Latin grammar rules.

One of the Latin rules that survives in English is the ban on ending a sentence with a preposition.

But some of the most common phrases in everyday English ignore the rule.

Who are you talking to? I don’t know what you’re talking about. Who are you waiting for?

Did you notice how all of these sentences end in prepositions? If you followed the Latin grammar rule, they would sound like this:

To whom are you talking? I don’t know about what you are talking. For whom are you waiting?

As you might hear, these sentences sound overly formal, even a bit snobbish. The word order, borrowed from Latin, does not feel natural in English.

Fortunately, the prohibition against ending a sentence with a preposition is disappearing. A large number of writers and editors say it is acceptable to end a sentence with a preposition. The Economist, a 150-year-old British news magazine, called the rule “an invented bit of silliness rightly ignored by many excellent publications.”

Whom as an object pronoun

Another rule that is disappearing is the requirement of using whom when referring to an object pronoun.

Whom is the object form of who. Grammatically speaking, whom has the same function as other object pronouns, such as me, him, her, and them. For example, “There’s the man about whom I was speaking.”

If you put a preposition before whom, you can easily avoid ending a sentence with a preposition. For example, “Who did you go with?” becomes very the formal “With whom did you go?”

Does all this sound unnecessary and confusing?

It is.

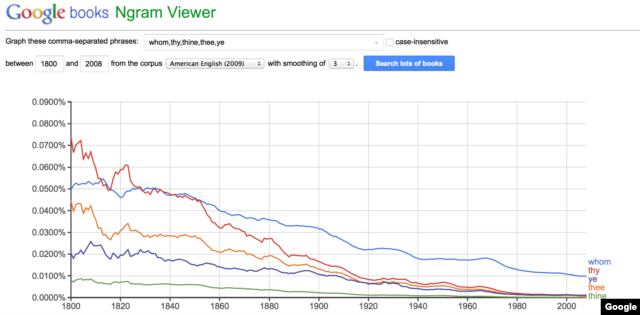

Fortunately, whom is rarely used in spoken American English today. More and more publications have stopped using it. In fact, whom has been dying for the past 200 years.

But it still has a place in formal writing. And test makers often make questions with whom to confuse students. A few pronouns have died completely, including ye, thee, thy, and thine. They do, however, still appear in religious texts and classic literature.

Their cannot be used with a singular pronoun

A third dying rule involved third-person pronouns. English does not have a single word to say both he and she. In other words, there is no gender-neutral singular third-person pronoun. So what do you say when you do not know if someone is male or female?

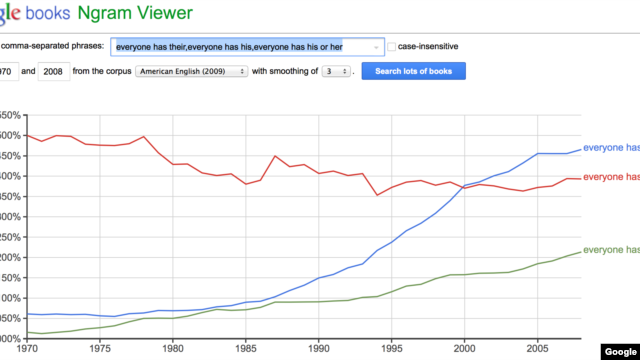

In the past, people used the male pronoun he to refer to all people. “Every student has his own opinion.” In later years, his or her came into use. “Everybody has his or her own opinion.” The change from his to his or her reflected the power of the women’s movement in the 1970s.

But many speakers found that his or her sounded a little strange, especially in conversation.

Today more people say, “Every student has their own opinion.” This example uses the plural their with the singular student. Their means the subject could be male or female. But it breaks a very old and very basic grammar rule: Pronouns and their antecedents are supposed to agree in number.

But when you say, “Every student has their own opinion”, the singular student does not match the plural their. So is it wrong to say, “Every student has their own opinion”? Well, it depends on who (or whom!) you ask.

More and more mainstream media organizations are allowing they, them, and their as a gender neutral pronoun. But disagreement remains. Like fashion and etiquette, grammar changes over time.

Why not invent a gender neutral pronoun for English? After all, languages like Swedish and Indonesian have one. Plenty of people have tried. However, more than 100 attempts to create a gender neutral pronoun in English have failed.

I’m Jill Robbins.

And I'm John Reynolds.

What do you think about these disappearing grammar rules? Will you miss them?

Adam Brock wrote this story for VOA Learning English. Jill Robbins and Kathleen Struck were the editors.

Words in the Story

snobbish – adj. having or showing the attitude of people who think they are better than other people : of or relating to people who are snobs

gender neutral – adj. a word or expression that cannot be taken to refer to one gender only

antecedent – n. a thing that comes before something else

mainstream – adj. the ideas, attitudes, or activities that are regarded as normal or conventional; the dominant trend in opinion, fashion, or the arts

etiquette – n. the customary code of polite behavior in society or among members of a particular profession or group