STEVE EMBER: I’m Steve Ember.

BARBARA KLEIN: And I’m Barbara Klein with EXPLORATIONS in VOA Special English. Visitors to Washington, D.C. this summer can see a powerful exhibit that tells about a dark period in American history. The exhibit at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery is called “The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942-1946.” It shows more than one hundred objects made by Japanese-Americans.

They were forced into internment camps by the United States government during World War Two. The objects made by these detainees helped to brighten their lives during a difficult period. And, they show the strength of the human spirit in surviving terrible conditions.

(MUSIC)

STEVE EMBER: To understand the meaning of this exhibit, we start with a little history. In the spring of nineteen forty-two, the United States government began carrying out an executive order to imprison Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast. About one hundred twenty thousand people of Japanese ancestry were forced to leave their homes and businesses. They were moved to ten rural detention centers, mainly in western states. Two-thirds of these people were American-born citizens. The government described the action as a military necessity to protect against spying or sabotage while the United States was at war with Japan.

BARBARA KLEIN: The internment program was a reaction to the Japanese bombing of the American naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. This event in December, nineteen forty-one resulted in the United States’ entry into World War Two.

But experts say the idea to create internment camps was also rooted in a general prejudice towards Japanese immigrants that started long before the war.

The government did not give Japanese-Americans much time to go to resettlement centers. They were forced to leave behind most of what they owned. For the first months, detainees were forced to live in temporary housing at “assembly centers.” During this time, the United States military built more permanent detention centers. Japanese-Americans would be forced to live there until nineteen forty-five when the war ended.

(MUSIC)

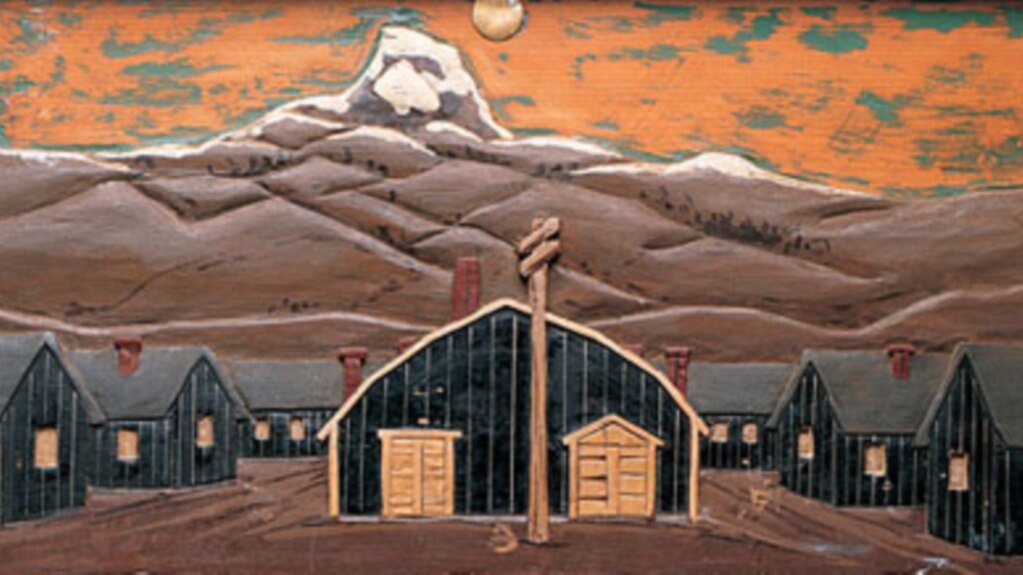

STEVE EMBER: One of the first objects in the “Art of Gaman” exhibit is a painting of a severe mountain landscape. At the base of these mountains is a detailed drawing of an internment camp. It is filled with small houses and surrounded by metal fences and guard towers.

The unidentified artist lived in this camp, the Tule Lake detention center in northern California. He did not have art supplies to make drawings. So he taped together two military command notices and drew on the back. This work is a good example of the inventive and creative ways that detainees found materials to make their art.

BARBARA KLEIN: Delphine Hirasuna organized the “Art of Gaman” exhibit. It is based on her book of the same name. She describes how she got the idea.

DELPHINE HIRASUNA: "After my mom died, I was going through a box in the garage and when I looked inside, I saw this little bird pin.”

BARBARA KLEIN: Delphine Hirasuna says she never heard her parents discuss their life in detention. In two thousand, she found the bird pin carved out of wood. She started to wonder what other artistic objects had been made in the camps. She wanted to know more about the objects that had been put aside and forgotten because of their painful memories.

STEVE EMBER: Delphine Hirasuna says she began to understand that the objects made in the camps were representations of “gaman.” This Japanese word expresses the idea of accepting a difficult situation with bravery and honor. The detainees made the objects to express themselves artistically and do something worthwhile with their time. Many of the objects in the exhibit were made to be useful as well as beautiful.

DELPHINE HIRASUNA: “Because the only thing that was in their barrack was a metal cot and mattress ticking which they filled with straw. The first things they made were chairs, tables, someplace to put their clothes away. And then because they were there for three and a half years, as time wore on, they made things to beautify their surroundings.”

BARBARA KLEIN: One example is a table made of pieces of found wood. The artist used pieces of palm tree branches to give the table nice details. Other objects made from found materials include a board for washing clothes and a set of scissors and knives. There were few tools in the camps, so some men melted pieces of metal to make tools.

The detainees were extremely inventive about finding materials. In some camps, they were permitted to explore the land to find natural materials.

DELPHINE HIRASUNA: “Two of the camps were over ancient sea beds. And they discovered that there were millions of shells on the ground. You could just scratch the earth and they said you could pick up buckets. There was a slate quarry at one of the camps. People picked up slate and carved the teapots and things.”

STEVE EMBER: A glass case in the exhibit holds a collection of pins that people wore on the front of their clothing. They look like flowers, until you look more closely. Detainees in two of the camps made them with small shells that they painted to look like flower arrangements. There were no real flowers for detainees to use in ceremonies like funerals and weddings. So, they would make their own flowers.

At another camp, detainees used different colored pipe cleaners to make large flower arrangements.

One extremely detailed container for holding cigarettes is woven out of an unusual material. The artist tied together pieces of string from a bag that was made to hold onions.

BARBARA KLEIN: Professionally trained artists made some of the works in the exhibit. For example, Sadayuki Uno had studied at the California College of Arts and Crafts. During the war, he was detained in Jerome, Arkansas. In the camp, he carved objects out of wood. He made four small carvings that looked like the faces of four leaders during World War Two: Benito Mussolini, Josef Stalin, Adolph Hitler and Winston Churchill. These carvings are very expressive and lively.

STEVE EMBER: Before the war, Chiura Obata was an art professor at the University of California, Berkeley. Mister Obata helped start an arts program for detainees in his camp. He found other professional artists at the camp to help teach. Mister Obata also kept a detailed record in his drawing book. The drawings show what life was like during the forced move and detainment of Japanese-Americans.

Several of his sketches are in the exhibit. One shows Mister Obata’s wife, Haruko, sitting on the train that took them from a temporary camp to their long-term camp in Topaz, Utah. Another drawing shows an old man bent over, trying to reach for a small dog near a metal fence. The old man was unable to hear, so when prison guards warned him to halt, he did not stop. The guards shot the man because they believed he was trying to escape.

(MUSIC)

BARBARA KLEIN: Jewel Okawachi’s parents were also detained during the war. Her father made dental devices during his detainment. She says people in the camps gave him the objects they had made as payment for his services. She kept the shell jewelry, bird pins and carved objects her parents collected over the years.

Miz Okawachi does not know the identity of the artists who created the objects. But she says she believes they would be happy to learn their work was on exhibit. And she says “The Art of Gaman” pays a welcome honor to her parents.

JEWEL OKAWACHI: “The only time I feel bitter is what it did to my parents. Because they came to this country for freedom, you know, and to make a better life for themselves and this happened.”

BARBARA KLEIN: She says many people would ask her father why he was not an American citizen, but he would never answer the question.

JEWEL OKAWACHI: “Having your freedom taken away from you is really something that is hard to forget.”

STEVE EMBER: No Japanese in the United States was ever found guilty of sabotage or treason during World War Two. But, it took more than forty years for the United States government to officially apologize for its actions. This apology resulted from a campaign organized by the Japanese-American community.

In nineteen eighty-eight the United States passed a law admitting the injustice. The act also gave each surviving victim of internment twenty thousand dollars.

Delphine Hirasuna says in her book that her aim has been to honor the experience of Japanese-Americans in the camps. She says the objects in this exhibit show their strong will and resourcefulness as well as their spirit and humanity.

BARBARA KLEIN: This program was written and produced by Dana Demange with reporting by Susan Logue. I’m Barbara Klein.

STEVE EMBER: And I’m Steve Ember. You can comment on this program on our website, voaspecialenglish.com. Join us again next week for EXPLORATIONS in VOA Special English.