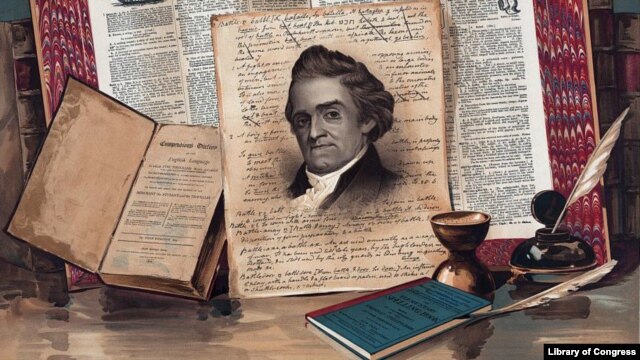

Some people collect stamps. Others collect coins. Noah Webster, Jr. collected words.

He did not save just the words, of course, but also their meanings and spellings. His collection became the basis of today’s American English.

Who was Noah Webster?

Webster was born October 16, 1758, on a farm in West Hartford, Connecticut. His family came from the early European colonists of Massachusetts and Connecticut.

Webster was interested in language even as a child. He learned to read before he started school.

Most children at the time stopped their education after only a few years. But Webster continued his. He attended college at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

During the four years Webster studied at Yale, the American colonies separated from Britain in the Revolutionary War. People at the time argued about the language of the newly independent states. Should it be English or German? After all, 10 percent of the population spoke German.

Others said Hebrew should be the common language. Many schools taught Hebrew so students could read the original Judeo-Christian Bible.

Webster thought the language of the American states should be English. But not British English. American English. The only problem was that such a language did not yet formally exist. People in different American states used different words, different spellings and different pronunciations.

The American Spelling Book

By this time, Webster was a teacher. Most schools taught Latin, and students wrote or made oral presentations in Latin.

But Webster argued that it was more practical for “merchants, mechanics, planters, etc.” to know their own language well. If they learned another language, he said, it should be a living language such as French, Italian, Spanish or German.

Webster believed improving children’s education could help build a stronger nation. In an essay, Webster wrote that Americans should study other countries’ histories and governments. That way, Americans could avoid mistakes, advance the sciences, and “add dignity” to the United States and human nature.

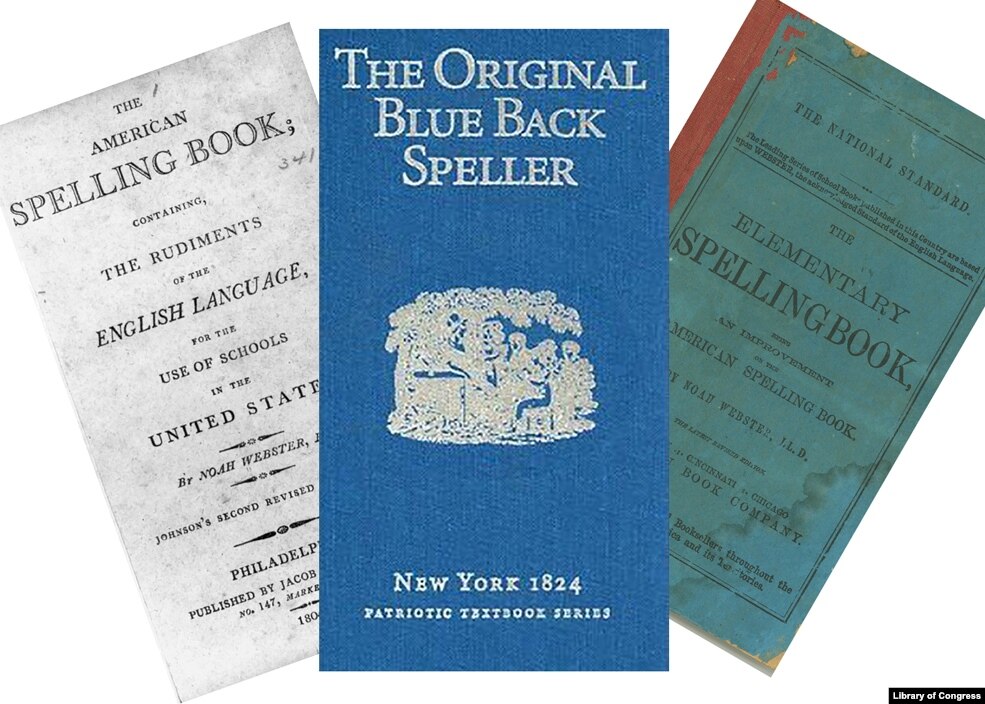

Young Americans should also learn to use a standard and pure language, Webster said. So he decided to write a series of textbooks: a speller, a reader and a grammar. Webster published the first book, which came to be called the Blue-Backed Speller, in 1783.

Webster worked hard to promote the book. He invented the modern book tour. He traveled around the country, bringing books to his public speeches.

The speller immediately became a best seller. Soon it was used in schools in every state. In 1787 Webster changed the book’s name to The American Spelling Book.

An important part of the method Webster taught for spelling was to divide a word into its sounds, or syllables. Thomas Dilworth’s British spelling books said that people should pronounce “ti” before a vowel as a separate syllable. That rule made them say nation as “na-ti-on” and motion as “mo-ti-on.” Webster thought the correct pronunciation was “na-tion” and “mo-tion.”

Webster also thought some British spellings did not make sense. He preferred variations that some Americans were already using. So in his works, he changed musick (spelled m-u-s-i-c-k) to music (m-u-s-i-c) and plough (spelled p-l-o-u-g-h) to plow (p-l-o-w).

Some of the changes he suggested did not stay – such as changing tongue (spelled t-o-n-g-u-e) to tung (t-u-n-g) and women (spelled w-o-m-e-n) to wimmen (spelled w-i-m-m-e-n). But many others remained.

American writer H. L. Mencken wrote in the early 20th century, “The influence of his Speller was really stupendous. It … maintained its authority for nearly a century.”

In the 100 years after the Blue-Backed Speller came out, the only book to sell more copies in the U.S. was the Bible. Webster’s speller helped unify the written language of the United States.

The American Dictionary of the English Language

Webster used the money he was able to earn from his speller to begin another project: a dictionary.

He believed Americans needed a dictionary that reflected their own geography, political system and history. His first version, published in 1806, included about 40,000 words.

His second, called the American Dictionary of the English Language, included 70,000 words. To create it, Webster learned at least the basics of over 20 languages.

He also defined words that were new to American English. Many were borrowed from Native American languages, such as “skunk” and “squash.” He also gave the pronunciation of words as Americans said them.

One of his definitions showed how proud Webster was of his country. He included a quote from its first leader, George Washington.

After the word “American,” Webster wrote: “A native of America; originally applied to the aboriginals, or copper-colored races, found here by the Europeans; but now applied to the descendants of Europeans born in America. ‘The name American must always exalt the pride of patriotism.’ Washington. ”

Webster’s dictionary came to be a symbol of the country’s new national identity. The website ConnecticutHistory.org points out that Webster’s efforts also marked the last time one person created a major dictionary alone.

A few years after Noah Webster died, at the age of 86, two brothers gained the rights to the American Dictionary. George and Charles Merriam owned a printing and bookselling business. They were able to make, update and sell the dictionary at a less expensive price than the Webster family had.

The reference book became increasingly popular in schools and homes across the U.S. Like Webster’s speller, Webster’s dictionary became the authority on American English – not just in the 19th century, but today. For example, if you are reading this article on a computer, point the mouse to any word in the story. You will see a definition from – you guessed it – Merriam-Webster.

I’m Jill Robbins.

Dr. Jill Robbins wrote this story for Learning English. Kelly Jean Kelly was the editor.

Words in This Story

standard – adj. regularly and widely used, seen, or accepted; not unusual or special

pure – adj. not mixed with anything else

syllable – n. any one of the parts into which a word is naturally divided when it is pronounced

variations – n. something that is similar to something else but different in some way

stupendous – adj. so large or great that it amazes you

version – n. a form of something (such as a product) that is different in some way from other forms

skunk – n. a small black-and-white North American animal that produces a very strong and unpleasant smell when it is frightened or in danger

aboriginals – n. the original people to live in an area

exalt – v. to raise (someone or something) to a higher level

In the quiz to the left, we have a fun spelling test for you. See if you can guess the correct spellings from Noah Webster's day.

Now it's your turn. What are some American words and spellings that have surprised you? Write to us in the Comments section or on our Facebook page.