Alexander Hamilton was not a U.S. president, but he was one of the most important early leaders of the U.S.

He fought in the Revolutionary War, wrote powerful arguments to persuade the states to accept the Constitution, and helped create the country’s national banking and economic system.

In 1929, the Treasury Department even put Alexander Hamilton’s face on the $10 bill. And in 2015, the musical “Hamilton” became one of the biggest shows on Broadway.

(MUSIC)

But the story of Hamilton’s early life did not make this legacy likely.

A difficult beginning

Hamilton was born in 1755 to poor, unmarried parents in the West Indies. He was a bright child and read every book given to him -- in English, Latin and Greek.

Hamilton also learned a great deal about business and economics. He talked about becoming a political leader in the North American colonies.

When Hamilton was 11 years old, his mother died. Hamilton got a job as an assistant bookkeeper. He learned how to keep financial records.

Even though his situation was difficult, others recognized that Hamilton was smart and talented. Hamilton’s boss sent him to New York. He became a student at King’s College, later called Columbia University.

Right hand man

The American Revolution gave Hamilton the chance to show his abilities. Hamilton supported the colonies’ war of independence against Britain. He became an aide to the colonies’ lead general, George Washington.

Even though Hamilton was young – in his early 20s – Washington trusted him as an excellent writer and thinker. Hamilton wrote the general’s letters. He had to use all his political and communication skills to get money and supplies for the Revolutionary Army.

Love and marriage … and money

During the war, Hamilton married Elizabeth Schuyler. She was a member of one of the nation’s wealthiest families.

Over time, Eliza and Alexander Hamilton made homes in New York and Philadelphia and raised eight children.

Bank of the United States

After the Revolutionary War, Hamilton became a lawyer in New York. He used the power of his pen again – this time, to defend the U.S. Constitution.

Hamilton was one of the authors of “The Federalist Papers.” The series of newspaper articles urged the newly independent states to adopt the Constitution and create a strong central government.

After the states agreed to ratify the Constitution, George Washington became the country’s first president. He asked Hamilton to be the first Secretary of the Treasury.

The role of Secretary of the Treasury was critical in the early days of the new nation. America’s most urgent problem was figuring out ways to pay its debts. The country had borrowed or promised a lot of money during the Revolutionary War.

Hamilton proposed a national bank. Congress approved the idea in 1791. The bank had $10 million in capital. It could lend the government money and pay off state debts. Hamilton’s system also created a federal system to collect taxes.

But not everyone accepted Hamilton’s views. Many of President Washington’s advisors – called his cabinet – opposed Hamilton.

Opponents expressed many objections to Hamilton’s Bank of the United States. Generally, members of Congress from the northern states supported the idea, while those from southern states opposed it.

Another political leader, Thomas Jefferson, said the Bank exceeded the powers of the Constitution.

Hamilton defended the Bank. He argued for a broad interpretation of the Constitution. He thought it permitted the federal government to do what it needed to do to strengthen the country’s economic system.

Hamilton largely won his political arguments. He became the leader of nation’s first political party, called the Federalist Party.

The Federalists, located mainly in the commercial Northeast, supported a strong national government. They laid the foundation of a national economy, created a national judicial system and set up principles of foreign policy.

Trouble again

But while Hamilton’s public life was succeeding, his private life was running into trouble.

Hamilton confessed to having an affair – to not being faithful to his wife. His oldest son fought a duel to defend Alexander Hamilton’s honor and was killed.

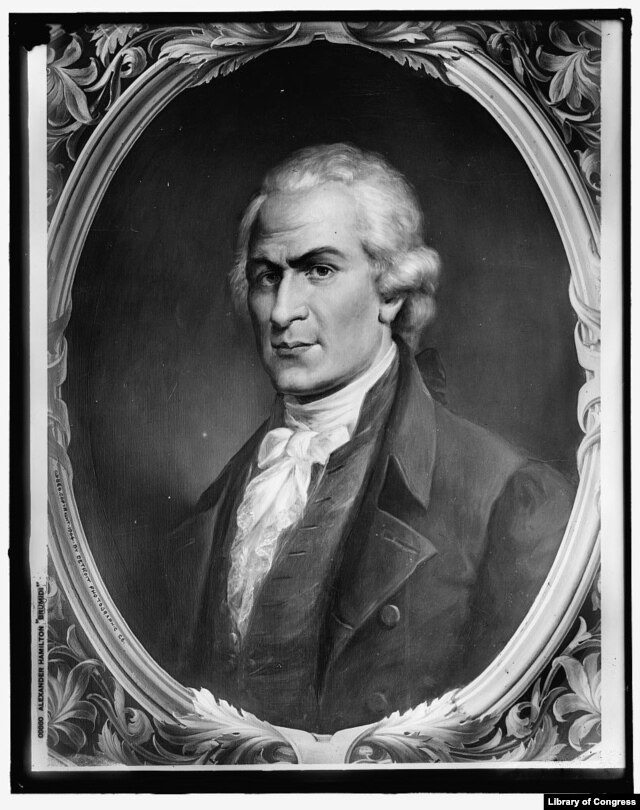

Hamilton eventually resigned from George Washington’s administration. And he publicly disagreed with other politicians, including the new president, John Adams, and a man named Aaron Burr.

Many who disagreed with Hamilton united in an opposition party called the Republicans, or sometimes the Democrat-Republicans. Thomas Jefferson was their leader.

Even though Hamilton and Jefferson disagreed about most things, in the presidential election of 1800 Hamilton supported Thomas Jefferson over the other leading candidate, Aaron Burr. Hamilton trusted Jefferson not to abuse the power of the presidency.

But Aaron Burr was angry that Hamilton had cost him the election. Later, when Burr ran for governor of New York, Hamilton opposed him again. Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel.

Duel to the death

At dawn on July 11, 1804, Hamilton and Burr fought a duel on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River, near Manhattan. They fired pistols from ten paces. Hamilton fell to the ground. He was carried to his Manhattan home and died the next day.

Just three years earlier, Hamilton’s son had been shot on the same spot.

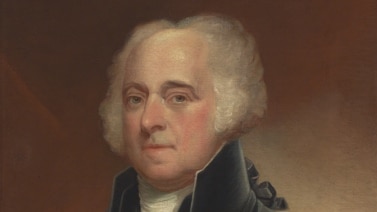

Today, Americans remember Alexander Hamilton as the architect of America’s banking and economic system. He was the first secretary of the treasury and created America’s central bank.

Hamilton’s system gave the new nation the ability to issue paper money, lend the government money and promote business and industry by extending credit.

Even though many disagreed with the power Hamilton gave the central government, he helped place the United States on an equal financial footing with the nations of Europe.

I’m Jonathan Evans.

Kelly Kelly and Mary Gotschall wrote this story for “The Making of a Nation” at Learning English. Kathleen Struck and Hai Do were the editors.

Did you know all this information about Alexander Hamilton? Let us know what you think in the Comments section below, or on our Facebook page.

Words in This Story

argument – n. a statement or series of statements for or against something

legacy – n. something that happened in the past or that comes from someone in the past

bookkeeper – n. a person whose job is to keep the financial records for a business

financial – adj. relating to money

wealthiest – adj. having a lot of money and possessions

ratify – v. to make (a treaty, agreement, etc.) official by signing it or voting for it

treasury – n. the place where the money of a government, club, etc., is kept

urgent – adj. very important and needing immediate attention

federal – adj. of or relating to a form of government in which power is shared between a central government and individual states, provinces, etc.

foundation – n. something (such as an idea, a principle, or a fact) that provides support for something

judicial – adj. of or relating to courts of law or judges

confess – v. to admit that you did something wrong or illegal

duel – n. a fight between two people that includes the use of weapons (such as guns or swords) and that usually happens while other people watch

resign – v. an act of giving up a job or position in a formal or official way

pace – n. a single step or the length of a single step — usually plural

architect – n. a person who designs and guides a plan, project, etc.

footing – n. used to describe the kind of relationship that exists between people, countries, etc.