This is the third article in a three-part VOA series on Islamist extremism in the United States.

In 2003, not long after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, the New York City police department began spying on Muslims.

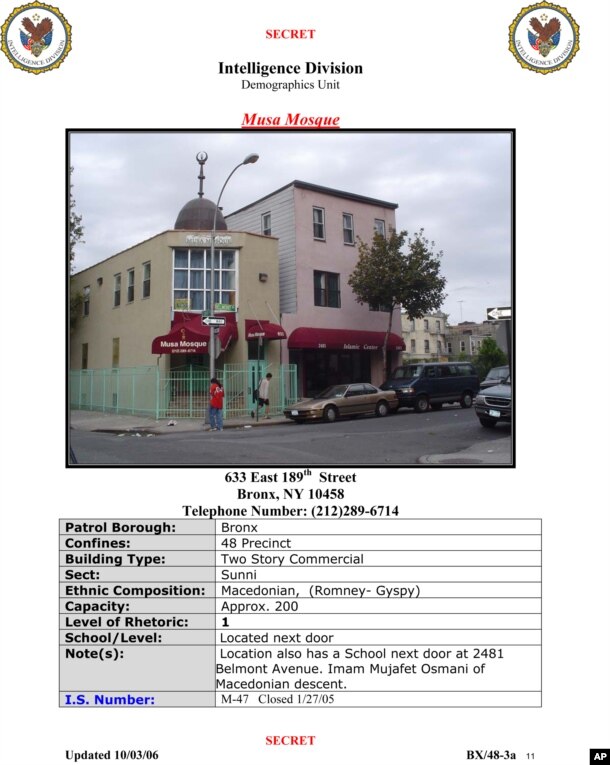

Officers in regular clothes visited Muslim businesses, student associations, charities and religious centers, called mosques. They believed a terrorist would be able to hide easily in those areas.

Then, the officers created a database about neighborhoods where people of 28 so-called “ancestries of interest” lived. The database included pictures, maps and information about the personal habits of Muslims in New York City.

When the public learned about the unit eight years later, many people objected. Some activists said the unit violated Muslims' civil rights. Objectors even filed two lawsuits against the unit, saying the police had discriminated against them.

In addition, the unit seemed not to work. Officers never used any of the information they gathered to identify someone who was likely to make an attack.

In 2014, shortly after he was elected mayor of New York City, Bill de Blasio ordered the unit to be closed.

But not everyone believes surveillance of Muslims in the U.S. should stop.

After Islamic State (IS) terrorist group attacks in Paris last November, and the release of a video suggesting New York would be attacked next, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump suggested the city should restart the program.

This month, after a gunman who said he supported IS killed 49 people at a nightclub in Orlando, Florida, Trump again talked about surveilling mosques and Muslim communities.

Communities, not spying

But none of the experts VOA interviewed for this report believed police should watch Muslims without a reason. They said law enforcement officials should become involved only when they suspect a crime is going to be committed.

These experts believe Muslim communities can police themselves. In other words, they say strong communities and families can help stop other Muslims from making mistakes.

And, they say professional police surveillance, such as the unit in New York City, actually makes Muslim communities and families weaker because it creates fear and mistrust.

Faiza Patel works at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School.

She told VOA that mosques have always welcomed strangers. Now, Patel said, guests and newcomers are often treated with suspicion. And many Muslims are nervous about being followed.

She said people have stopped using mosques as the center of the community. Instead, she said, “They will go in and they will fulfill their religious obligation, but then won't hang around. They go home.”

Patel said that, as a result, the Muslim community is losing its ability to stop other Muslims from committing crimes or terrorist attacks.

Families

Seth Jones is a terrorism expert at the RAND Corporation, a research group. He adds that families are a critical part of stopping people from extremist thinking and violence.

For example, the wife of Omar Mateen - the killer in Orlando this month - knew what he was planning to do. She was reportedly with him as he looked for possible targets, including Disney World and a shopping mall. Mateen's father also said he was worried about what his son might do.

But when the FBI investigated Mateen over the last three years, they found no clues he would walk into a nightclub and kill 49 people.

The FBI says Mateen's case is typical. About half the time, a family member knows a relative is becoming radicalized but does not know what to do about it.

Anne Speckhard is a research psychologist. She is the director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism. She said people specially trained in fighting extremism and radicalization can help families and communities.

For example, parents might not want to call the police and report their child. But they might call a special number and ask for help.

“Why would you call the FBI if they knew you were going to set up a sting operation?” Speckhard asked. “But you might call a hotline if you know they were going to send over a psychologist or an imam to talk to your kid and say, 'You know what? You really got Islam wrong here.'”

I'm Jonathan Evans.

VOA'sJeff Swicord reported this story from Washington. Christopher Jones-Cruise adapted it for Learning English. Kelly Jean Kelly was the editor.

We want to hear from you. Write to us in the Comments Section, or visit our Facebook page.

Words in This Story

ancestry - n. a person's ancestors; the people who were in your family in past times

commit - v. to do (something that is illegal or harmful)

fulfill - v. to do what is required by (something, such as a promise or a contract)

obligation - n. something that you must do because of a law, rule, promise, etc.

hang around - phrasal verb, informal: to be or stay in a place for a period of time without doing much

typical - adj. normal for a person, thing, or group; average or usual

sting operation - n. a complicated and clever plan that is meant to deceive someone especially in order to catch criminals

hotline - n. a telephone service for the public to use to get help -- sometimes, but not always, in emergencies

psychologist - n. a scientist who specializes in the study and treatment of the mind and behavior; a specialist in psychology

imam - n. a Muslim religious leader