Welcome to the MAKING OF A NATION – American history in VOA Special English.

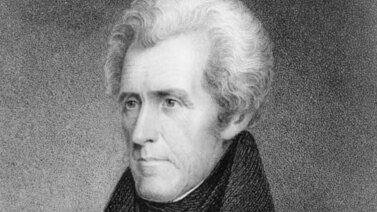

Andrew Jackson served as president of the United States from eighteen twenty-nine to eighteen thirty-seven. His first term seemed to be mostly a political battle with Vice President John C. Calhoun.

Calhoun wanted to be the next president. Jackson believed his secretary of state, Martin Van Buren, would be a better president. And Van Buren wanted the job. He won the president's support partly because of his help in settling a serious political dispute.

This week in our series, Harry Monroe and Kay Gallant continue the story of Andrew Jackson and his presidency.

VOICE ONE:

President Jackson's cabinet was in great disorder. Vice President Calhoun was trying to force out Secretary of War John Eaton. Eaton would not resign, and the president would not dismiss him.

Van Buren designed a plan to gain Eaton's resignation. One morning, as Jackson discussed his cabinet problems, Van Buren said: "There is only one thing, general, that will bring you peace -- my resignation."

"Never," said Jackson.

Van Buren explained how his resignation would solve a number of Jackson's political problems. Jackson did not want to let Van Buren go. But the next day, he told Van Buren that he would never stop any man who wished to leave.

VOICE TWO:

The president wanted to discuss the resignation with his other advisers. Van Buren agreed. He also said it might be best if Secretary of War Eaton were at the meeting.

The advisers accepted Van Buren's resignation. Then they went to Van Buren's house for dinner. On the way, Eaton said: "Gentlemen, this is all wrong. I am the one who should resign!" Van Buren said Eaton must be sure of such a move. Eaton was sure.

VOICE ONE:

President Jackson accepted Eaton's decision as he had accepted Van Buren's. But he was unwilling to give up completely the services of his two friends. He named Van Buren to be minister to Britain. And he told Eaton that he would help him get elected again to the Senate.

Jackson then dismissed the remaining members of his cabinet. He was free to organize a new cabinet that would be loyal to him and not to Vice President Calhoun.

Even with a new cabinet, Jackson still faced the problem of nullification. South Carolina politicians, led by Calhoun, continued to claim that states had the right to reject -- nullify -- a federal law which they believed was bad.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

Jackson asked a congressman from South Carolina to give a message to the nullifiers in his state. "Tell them," Jackson said, "that they can talk and write resolutions and print threats to their hearts' content. But if one drop of blood is shed there in opposition to the laws of the United States, I will hang the first man I can get my hands on to the first tree I can find."

Someone questioned if Jackson would go so far as to hang someone. A man answered: "When Jackson begins to talk about hanging, they can begin to look for the ropes."

VOICE ONE:

The nullifiers held a majority of seats in South Carolina's legislature at that time. They called a special convention. Within five days, convention delegates approved a declaration of nullification.

They declared that the federal import tax laws of eighteen twenty-eight and eighteen thirty-two were unconstitutional, and therefore, cancelled. They said citizens of South Carolina need not pay the tax.

The nullifiers also declared that if the federal government tried to use force against South Carolina, then the state would withdraw from the union and form its own independent government.

VOICE TWO:

President Jackson answered with a declaration of his own. Jackson said America's constitution formed a government, not just an association of sovereign states. South Carolina had no right to cancel a federal law or to withdraw from the union. Disunion by force was treason. Jackson said: "The laws of the United States must be enforced. This is my duty under the Constitution. I have no other choice."

VOICE ONE:

Jackson did more. He asked Congress to give him the power to use the Army and Navy to enforce the laws of the land. Congress did so. Jackson sent eight warships to the port of Charleston, South Carolina, and soldiers to federal military bases in the state.

While preparing to use force, Jackson offered hope for a peaceful settlement. In his yearly message to Congress, he spoke of reducing the federal import tax which hurt the sale of southern cotton overseas. He said the import tax could be reduced, because the national debt would soon be paid.

VOICE TWO:

Congress passed a compromise bill to end the import tax by eighteen forty-two. South Carolina's congressmen accepted the compromise. And the state's legislature called another convention. This time, the delegates voted to end the nullification act they had approved earlier.

They did not, however, give up their belief in the idea of nullification. The idea continued to be a threat to the American union until the issue was settled in the Civil War which began in eighteen sixty-one.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

While President Jackson battled the nullifiers, another struggle began. This time, it was Jackson against the Bank of the United States. Congress provided money to establish the Bank of the United States in eighteen sixteen. It gave the bank a charter to do business for twenty years. The bank was permitted to use the government's money to make loans. For this, the bank paid the government one and one-half million dollars a year. The bank was run by private citizens.

VOICE TWO:

The Bank of the United States was strong, because of the great amount of government money invested in it. The bank's paper notes were almost as good as gold. They came close to being a national money system.

The bank opened offices in many parts of the country. As it grew, it became more powerful. By making it easy or difficult for businesses to borrow money, the bank could control the economy of almost any part of the United States.

VOICE ONE:

During Jackson's presidency, the Bank of the United States was headed by Nicholas Biddle. Biddle was an extremely intelligent man. He had completed studies at the University of Pennsylvania when he was only thirteen years old. When he was eighteen, he was sent to Paris as secretary to the American minister.

Biddle worked on financial details of the purchase of the Louisiana territory from France. After America's war against Britain in eighteen twelve, Biddle helped establish the Bank of the United States. He became its president when he was only thirty-seven years old.

VOICE TWO:

Biddle clearly understood his power as president of the Bank of the United States. In his mind, the government had no right to interfere in any way with the bank's business. President Jackson did not agree. Nor was he very friendly toward the bank. Not many westerners were. They did not trust the bank's paper money. They wanted to deal in gold and silver.

Jackson criticized the bank in each of his yearly messages to Congress. He said the Bank of the United States was dangerous to the liberty of the people. He said the bank could build up or pull down political parties through loans to politicians. Jackson opposed giving the bank a new charter. He proposed that a new bank be formed as part of the Treasury Department.

VOICE ONE:

The president urged Congress to consider the future of the bank long before the bank's charter was to end. Then, if the charter was rejected, the bank could close its business slowly over several years. This would prevent serious economic problems for the country.

Many of President Jackson's advisers believed he should say nothing about the bank until after the presidential election of eighteen thirty-two. They feared he might lose the votes of those who supported the bank. Jackson accepted their advice. He agreed not to act on the issue, if bank president Biddle would not request renewal of the charter before the election.

Biddle agreed. Then he changed his mind. He asked Congress for a new charter in January eighteen thirty-two. The request became a hot political issue in the presidential campaign.

(MUSIC)

ANNOUNCER:

Our program was written by Frank Beardsley. Your narrators were Harry Monroe and Kay Gallant. Transcripts, MP3s and podcasts of our programs can be found, along with historical images, at voaspecialenglish.com. Join us again next week for THE MAKING OF A NATION - an American history series in VOA Special English.

This is program # 59 of THE MAKING OF A NATION